Miriam Wattles

University of California, Santa Barbara

It is not hard to know of the great men of Meiji; theirs is the de facto history. What about the Meiji musume (娘 daughters)—those girls who grew into women during that era of tumultuous change? On the whole, it is far easier to appreciate them on display—poised with their various accouterments in visual representations—than to learn very much of their social interactions and overall import. Yet there is no doubt but that these girls and women contributed an inestimable amount to the social fabric of their time. Their physical, mental and emotional labor—performing both in cultural and economic realms—was fundamental to the Meiji modernization project.

This short essay provides a perspective on the impact that these musume had on their times by looking inside the frames of five nishiki-e (錦絵)—woodcuts called “brocade pictures,” because of the way their multi-colored splendor recalled those sumptuously patterned fabrics. They date from 1874 to 1888, or the early Meiji, before photography began to predominate. The titles and explanations, the setting, and the people with their objects all about them tell much about the occupations and roles of women at the time. This selection highlights, further, what the stuff of their clothing tells us and how it teased their fancy. Women’s kimono and other apparel were their identity, means of communication, even their wealth. Yet since these popular and inexpensive prints were made to tease the viewer’s fancy or imagination, they cannot be entirely believed. We must be aware of the elaborate embroideries on these brocade pictures. They functioned, in many ways, like the “magic system” of advertising.[1]

As well, in considering their ‘stuff,’ we will consider the fundamental aspect of the makings of these textiles and garments. Although rare, a significant few depict girls and women involved in textile production in Japan, in cottage industries or in factories. The period was marked, in fact, by the shift from the former to the latter. Traditionally, cloth was currency in Japan (as elsewhere in Asia) and, during the Meiji period, women’s work producing textiles became, at least for some of them, oppressive national currency for export. Because the textile industry succeeded in making Japan competitive in the world market, these female textile factory workers can claim significant credit in the success of Japanese industrialization. Thus, we attend to clothing: from daughters of rural families, geisha, daughters of the best families known as ojōsama (お嬢様), to jokō (女工), as factory girls were called.[2] Augmenting the unreliable pictorial evidence, we tune our ear to key verbal accounts as well.

Impressions to Savor

Figure 1: Hiroshige III. Picturing the Products of Great Japan (Dai Nippon). Rikuchū no kuni yōsan no zu. Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L2:1 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here).

This print from a 1877 series by Hiroshige III highlights famous goods of each region. The series as a whole was meant to promote industriousness, collaboration, and inventiveness. Its title, “Picturing the Products of Great Japan (Dai Nippon),” makes the point that the regional production that was hitherto the pride of each local area now served the nation. Their manner of work, along with the visual tropes and conventions in this series, might well identify this as a print of the previous Edo period, since little had changed in a few generations. However, there is one obvious minor difference in the place names. This print depicts “Sericulture in Rikuchu” – a newly named district in the northeast now lying across Iwate and Akita prefectures. The explanation (set within the handscroll at the upper left) enthuses about the frames consisting of rows of bamboo pyramids, this region’s inventive device for nesting silk worms. Women, with their kimono sleeves fastened back with red tasuki (襷) ties, drop silkworms ready to spin cocoons into these frames. Three to four worms, it is explained, would readily spin their cocoon in each pyramidal space.

For centuries if not millennia, women had been engaged in sericulture all over rural Japan, as in much of Asia. As with spinning and weaving, this first step of cultivating the silk worms was women’s work. This labor-intensive multi-stepped process of feeding of the worms lasted just 28 days and traditionally was seasonal, undertaken once per year. It would bring in extra household income. The networks of cottage industries were extensive and although those who produced the cocoons might spin the thread, they often left the weaving to others.[3]

Given the constant poverty in the northeast, we can assume this harmonious and light-hearted scene is somewhat of an idealization of a country sericulture workshop in Rikuchu. The woman standing with the baby strapped to her back seems to be imparting good news to those seated, while someone’s son outside holds up his cat to enjoy the fun. Looking closely, we see hints of travel and commerce. Beyond the boy at the door, a traveller passes. Behind him in a rickshaw in the distance is perhaps the go-between in the local trade network. Only the wealthy rode in the new rickshaw (and indeed, this is another marker that this print dates to early Meiji). These beautifully patterned indigo and cotton kimono—most likely fancier and more varied than what was usually worn—would have been dyed with stencils. Although the fabric might have been woven and dyed in the area, for some time already cotton kimonos had been increasingly made of imported fabrics. What remained consistent for a long while, in most households, was the expectation that women would stitch together and care for her family’s garments.

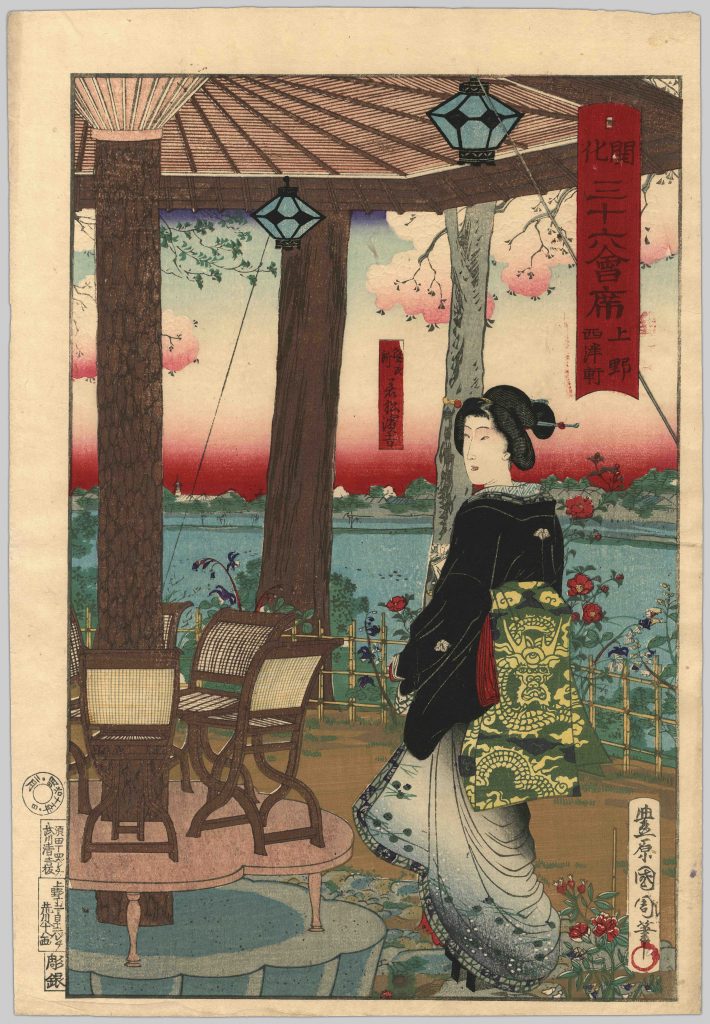

Figure 2: Kunichika, 1878. Enlightened 36 gourmet spots: Ueno, Seiyōken. Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L3:4 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here).

From the patio at the Seiyōken restaurant on the hill of Ueno above the famous Shinobazu pond, a lone figure gazes back towards us. She is a geisha, identifiable by her hairdo and the way she lifts the skirts of her fine gown to show her high geta footwear. Dusk descends in the sky from the distant banks below, displaying a lovely gradation from a deep regal red to pink; this same pigment (known now as “Meiji red”) tints camellia blossoms while in a lighter intensity, it becomes subtle eye- shadow and tints the edges of the plum blossoms. The camellia and plum blossoms tell us that it is very early spring; the scattered pine needles and pinecones in a sprinkling of snow lining the graduated bottom of the geisha’s kimono communicate new-year auspiciousness. The ivy crest at the top of her kimono—from a fine silk probably dyed in the exquisite stenciled paste resist dyeing yūzen technique of Kyoto—asserts her house affiliation. The magnificent gold embroidered dragon descending from her obi (sash) expresses her innate fierceness, dash, and nerve. This print is from a series touting the 36 enlightened restaurants for kaiseki (会席a multi-course meal) in Tokyo. Yet a geisha’s celebrity does the promotion. If not a recognizable famous personality, this geisha embodies the ideal of Meiji chic.

Employing all of the conventions of the bijinga (美人画 beauty picture), this would not be recognizable as a Meiji print except for this Meiji red, the insertion of the word “enlightened” 開花 (kaika) in the title and, most odd to us now, the arrangement of chairs perched upon a low table that in turn stands on a stone dais next to her. This type of dais is a hamadai (浜台). Long ago used at the most formal ceremonies, it had come to be used for any grand occasion. Here, however, the dais displays the new furniture of the west. Whether these chairs were meant to be used or not is a puzzle not easily solved. It is certain that a very special meeting is about to commence during the New Year’s season.

Now a set stereotype of Japan, geisha are usually denied any history. Geisha were not always the leading ladies of the night in Japan, but rather grew more popular during the nineteenth century to reach their height during the early Meiji period. And where and how they were prostitutes or not is a question impossible to answer since “geisha” could mean many things.[4] Yet it is true that the highest echelon of geisha accompanied the important men of the era to public events and galas of the time, as well as entertaining at private parties. Some of them became wives to these men. As Mio Wakita argues, the glamorous geisha typifies the self-created stereotypes of Japan.[5] They were certainly celebrities to foreigners and Japanese alike. They performed for tourists in Kyoto; one of them, Sadayakko, went with a troupe of actors and dancers to cities in the US and Europe to reach great acclaim abroad. Gradually, as love marriages were increasingly promoted in Japan, they grew to be a site of cultural friction. Yet they were the first models for advertisements. Certainly, many daughters of Meiji, whatever their position in life, would find cause to savor the pictured geisha’s taste in dress. Surely the female viewer would imagine herself there, dressed to the nines as she waits for important guests in this exotically Western restaurant.

Impressions to Emulate

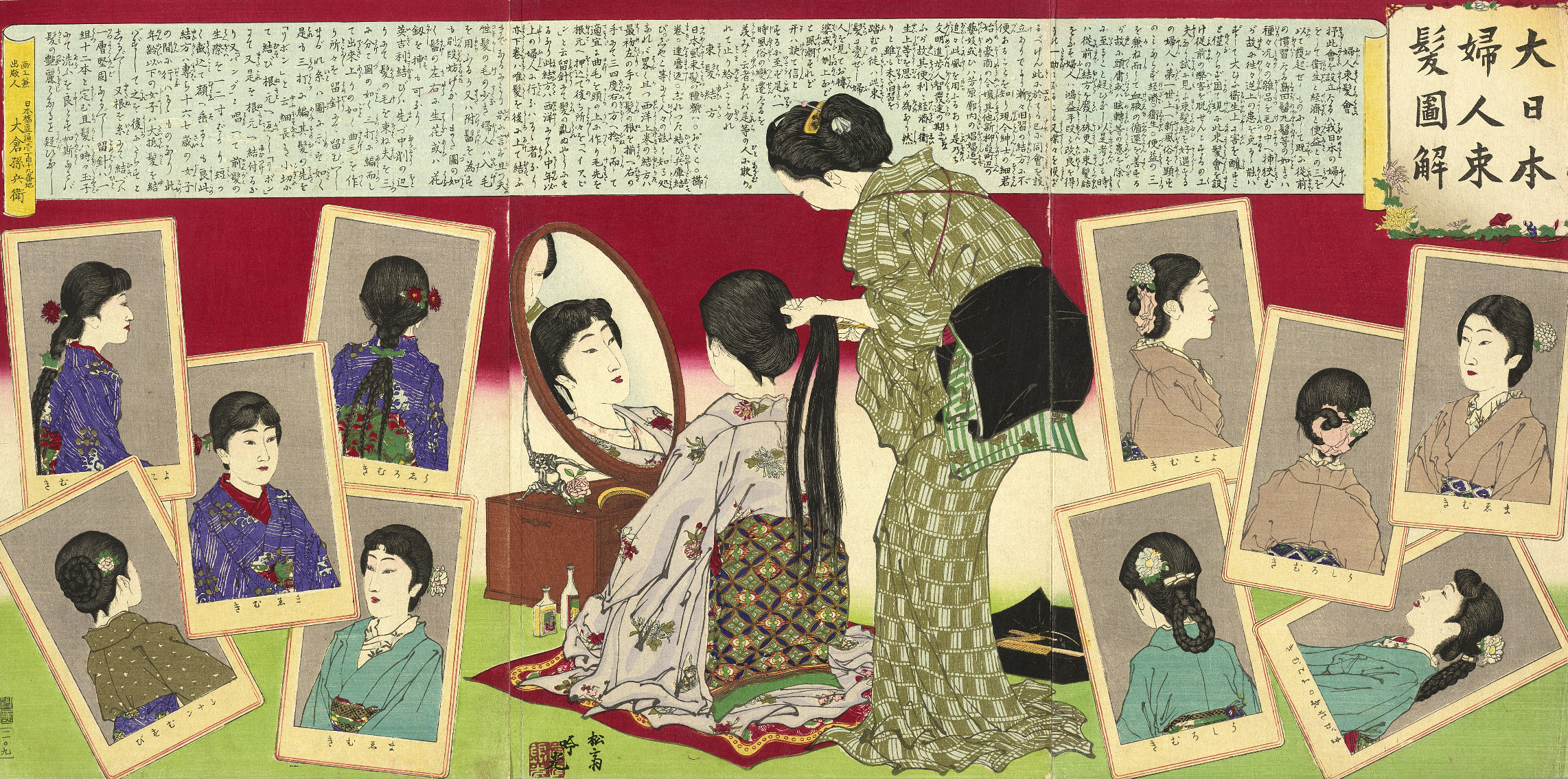

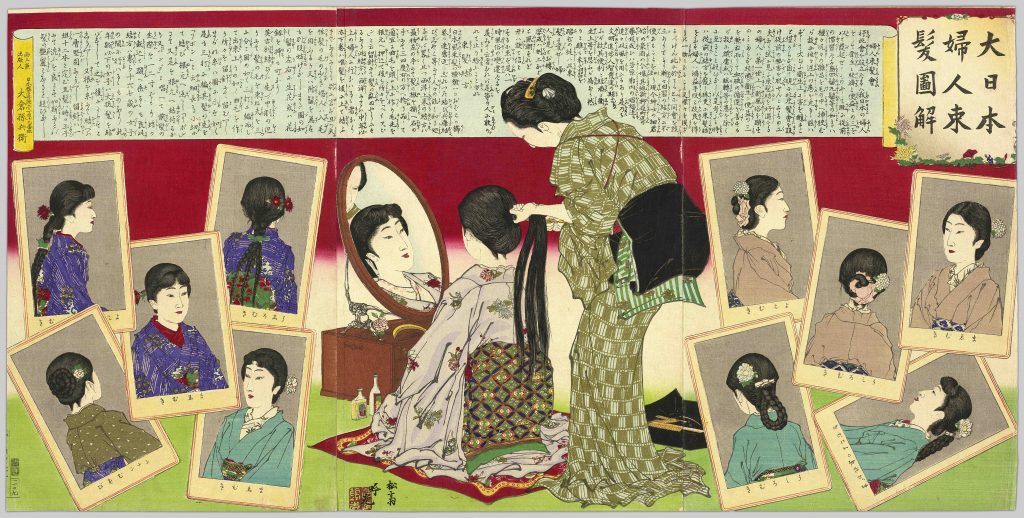

Figure 3: Adachi Ginko, 1885. A pictorial explanation of hairdos for Great Japan. Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L3:3 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here).

During the 1880s Westernization became de rigueur. This triptych (consisting of three prints bought separately) by the prolific and versatile artist Adachi Ginkō espouses a new “Hairdo Association” to boost Westernized hairstyles over past modes. As opposed to the previous print that entices the viewer with a bit of Westernized furniture, this one contains definite guidelines for change. As it says in the long scroll hanging above, the three main reasons to abandon the old Shimada-mage or Maru-mage hairdos were because the Western hairstyles were 1) hygienic, 2) economical, and 3) convenient. It notes that these Western styles had the virtue of not needing the elaborate hairpins or ornaments of old. The explanation goes on to introduce “bangs” while detailing concretely how one twisted, divided, and braided the hair for either hanging styles or buns. It ends by advising occasional shampoos with an egg to make one’s hair shiny and radiant.

One sees the first basic step to these hairdos in what is being done to the central seated figure. From gathering and dividing the hair just so, one can create all of the styles described: both in the text, and depicted in the photograph-like pictures of women of various ages. The hairstyles are shown methodically from the back, from profile, and in three-quarters view. The younger ones display bangs. In a light lavender silk kimono with a design of scattered flowers and an obi of a rich brocade of medallions, a young lady has her hair done by a kamiyui (髪結 a woman hairdresser). The kamiyui wears a silk kimono with a stencil-dyed olive vertical pattern.

Surely female viewers were expected to yearn to be this seated young lady with her long, beautifully featured face reflected in the mirror. Just as surely, they were meant to follow these styles—whether they were in a position to join this publicized association or not. But what is the status of the young lady getting her hair done? Is she ojōsama, one of the musume of higher-class families? Even if an ojōsama, she blurs the line, looking very geisha-like in her beauty and daring. How many ojōsama would use the services of kamiyui? The black velvet obi turned inside out like a geisha suggests the kamiyui might have been a geisha herself. Many, including the daughters of the best families, were chided at the time for following the fashions of the geisha.

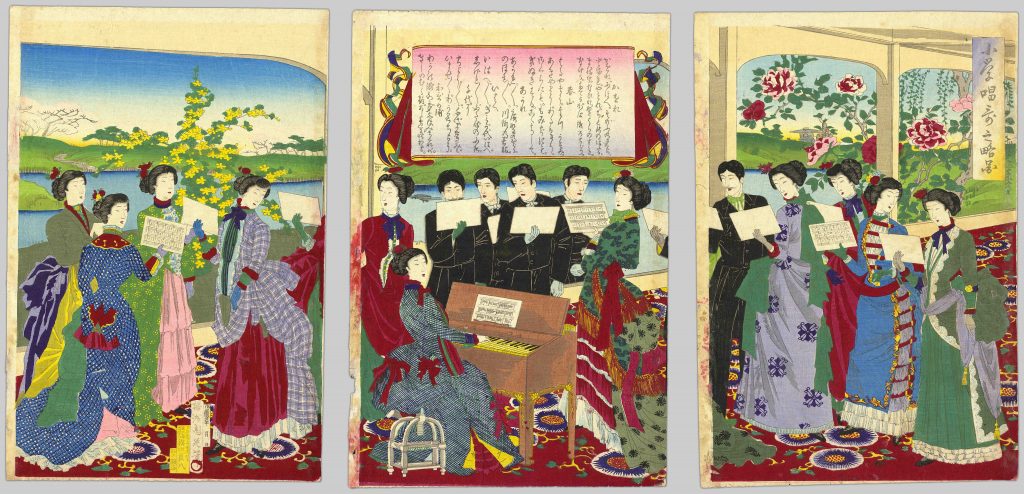

Figure 4: Hashimoto Chikanobu, 1887. Shōgaku shōka no ryakuzu. Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L3:2 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here).

Two years later, and we are at the height of the adoption of Western fashion, in a Western-style venue. We are made to feel the charm of a new amalgamated music emanating from this salon. A chorus of ladies and five men accompanied by an elegant pianist perform songs from the widely popular elementary school songbook. Since its release six years before, the songbook had spawned sequels and been reprinted repeatedly. There was virtue to be gained from this new national music, a product of collaboration between a foreign advisor and court officials. With the lyrics to six songs in the central cartouche, we might even join in. The words to the first song begin: “Be fragrant, let out your smell, [you] cherry blossoms in the garden! Stop, flicker, you fireflies in the grasses! Beckon, sway, you reeds in the field! Perch, flutter, you plovers of the river bank!”[6]

The vista outside reveals a pond surrounded by flowers outside of the arches, flowers in the ladies’ chignons lightly pick up on the spring cherry blossoms, yamabuki, and peonies outdoors. The deep red of the regal carpet with its flower medallions suggest this location is the famous spot associated with the peerage, the Rokumeikan. This building, designed by the British architect Josiah Conder, was the venue for the dance parties, musical evenings, and genteel games during the 1880s, at a time there were still many Western dignitaries, teachers, advisors, and other assorted adventurers in Japan. The women in their grand robes seem to relish their performance in this setting.

This triptych served palpably as a fashion plate. The role of leading women as cultural stewards necessitated that they perform socially in the foreign manner. And whereas men could display their elegance in this soiree culture by wearing black tailcoats and trousers, a style slow to change, women were obliged to dress according to the mode of the moment. This was less individual choice than something dictated from above. In January of 1887, the year this print came out, the empress had just put out a proclamation to advise women to adopt contemporary Western women’s wear. For the benefit of the country, and to facilitate new western manners such as bowing, she advocated the adoption of the “Western method of sewing.” The proclamation continued:

In carrying out this improvement …be especially careful to use materials made in our own country. If we make good use of our domestic products, we will assist in the improvement of techniques of manufacture on the one hand, and will also aid the advancement of art and cause business to flourish. Thus the benefits of this project will reach beyond the limits of the clothing industry.[7]

And indeed, the print depicts fabric patterns that might well have been spun, woven and dyed in Japan (for example, the blue cloud motif on the dark green top donned by the lady standing to the right of the piano is an ancient Sino-Japanese motif).[8]

The ladies’ sacrifice for Japan through fashion was no small burden. 1887-88, the years when Westernized fashion in Japan were at a height, were the pinnacle of fashion for the bustle. Thus, these ladies had to not only take on the weight of copious layers of fabric, but also distort their figures into the unnatural shape dictated by the bustle. Additionally, even though dresses could be ordered from both native and foreign dress designers in Tokyo, it was difficult to afford for many of the public servants required to wear them.

Yet there were some women who stepped into leadership roles and naturally wore the dress to fit. These events featuring Western music would have been impossible without the few daughters of dignitary families who had been sent to study abroad. Perhaps the pianist in the print is modeled after Baroness Uryū, who had been sent as a girl to study in the US and who had studied music at Vassar College.[9] This rarefied world centering on the circles of court and government accords to the lifestyle of those who went to Gakushuin, the Peers College, as characterized by Alice Bacon in her 1891 book, Japanese Girls and Women.[10] Bacon came to teach at Gakushuin on the invitation of the pioneer in women’s education Tsuda Umeko, who also had studied in the US; Tsuda later founded Tsuda College for Women. These were the ojōsama of dignitaries, whose example was meant to encourage the rising middle class to marry well then become, as a well-repeated slogan put it, “good wives and wise mothers” 良妻賢母 (ryōsai kenbo).

Western dress for urban middle and upper class women was not in fashion for long. By the 1890s, most women were again wearing kimono, reinventing as fashion does, the traditional styles of times past.[11] Moreover, in the countryside the clothing had hardly changed at all, especially among the impoverished peasants who wore coarse work cloths, straw sandals, and whose children wore “ragtag, patched up, old clothes handed down from their older siblings.”[12]

A New Type of Female Labor

The Meiji government, in a first major effort to enrich the nation, launched the industrialization of textile machinery factories. In this, they followed in the lead of Great Britain, France, and the United States. What had been a sustainable female-dominated cottage industry with only short seasonal stretches of intensive labor (as seen in the first print) became year-round factory labor. The jokō (factory girl) was born.[13] If not so terrible at first, the pay soon descended to the cheapest possible level and working conditions became disgracefully bad. Jokō soon were a shunned group, not a suitable occupation for proper daughters. Why did they endure it? As the lines from one of many songs they sung puts it:

We do it for ourselves and for our parents.

Boys to the army,

Girls to the factory.

Reeling thread is for the country too.[14]

Yet, of course, the reasons were not always that idealistic and simple.[15]

The most famous of the textile factories, Tomioka Silk Mill—a filiature plant where silk thread was spun from cocoons—became a world heritage site in 2014. The Meiji government opened it in 1872 as a model factory. Choosing the town of Tomioka (130 kim northwest of Tokyo in Gunma prefecture) for its sufficient water and its already strong infrastructure in cocoon production, the government acquired state of the art machinery from France, and sponsored Paul Bonart, his wife, and an entire team to develop the effort. It was daughters of the old shizoku (士族), or samurai class, who first patriotically answered the government’s call for 16 girls from each prefecture. One of the samurai daughters who went to Tomioka Mill recounts her joy in learning as well as the trials of life there in her 1931 memoir Tomioka Diary (Tomioka Nikki). But she stayed less than a year before going back to her hometown to help supervise the establishment of a factory there.[16]

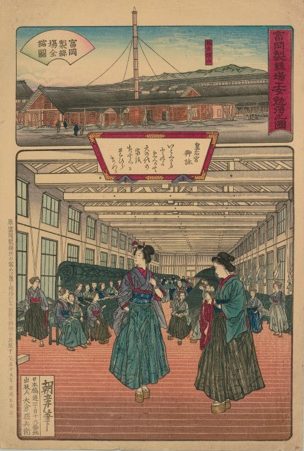

Figure 5: Choko, 1926 (1873) Tomioka seishijo kōjo benkyō no zu. Source: Gunma Prefectural Library (used by permission)(Click to enlarge).

We must be wary of the selectivity of cultural memory as it is filtered through representations. A print originally published in 1873 (but reissued in 1926) commemorated the inauguration of Tomioka Silk Mill. At the top is a portrait of the factory. Its brick construction was quite rare at the time. To mark the location, the distant mountains are labeled. A plaque segues the top outside view and the bottom interior of the factory. It contains the poem that the empress dedicated upon her official visit to the factory in 1872.

The hakama (袴 divided skirts) worn in the print tell an interesting story. Originally a court garment, then taken up by samurai, by early Meiji it distinguished the new figure of the schoolgirl. Front and forward two girls stand full of pride, the one on the right ready to fasten her haori (羽織 jacket) sleeves up with the tasuki. They are “first class girls” who, by spinning faster and better quality thread, had proven themselves above the rest, and so had higher geta, to literally stand taller than the others. According to the title of the print, they are about to start their lessons. That this factory was a place to gain an education, rather than be exploited for their labor, was a pleasant fiction used to recruit girls to the factory. And there is the question of how long or often the simple yet rich hakama as portrayed here were actually worn at the mill.

This print was not very representative of either Tomioka Silk Mill, which privatized by 1893, nor of the hundreds of similar factories that sprang up in the countryside and cities. The first phase when the majority of workers at Tomioka were samurai daughters soon passed. Almost all of the cheap female labor eventually came from impoverished rural areas. Families there, with too many mouths to feed and rising rents on their tenant farms brought on by political-economic changes, sent out their daughters to work from as young as seven years old. Their choices were limited. They might send their daughters to serve as komori, or “nursemaids,” to wealthier neighbors; they might “sell them” to a brothel to become geisha or lower prostitutes;[17] or, increasingly through the years, they would contract them out to distant dormitories to become jokō. In theory the contract was only up to a few years, but many worked for decades. Under heavy capitalistic pressure for higher profits, working conditions rapidly worsened. Because of the perennial problem of runaways, jokō were confined to the factory and their dormitories except for rare occasions; physical, sexual, and verbal abuse was common; and illnesses brought on by the harsh conditions often led to death.

Yet to be heard?[18]

Some of the Meiji musume, as well as some of those around them, recorded their stories and songs of sacrifice and self-valuation. The Tomioka Diary has been mentioned above. In 1925 Hosoi Wakizō captured the attention of many with his The Sorry History of the Factory Girls (Jokō Ai-shi), and his wife, a main informant, later published My Own Sorry History of Female Textile Workers (Watashi no jokō aishi).[19] In 1968, Yamamoto Shigemi put out Oh! The Nomugi Pass! (Aa! Nomugi tōgei!) out of extensive interviews with the women, now grandmothers, who had worked at a factory near lake Suwa factory, entitled for the precipitous Nomugi pass they had to cross to arrive at the factory. In 1979, this was turned into an epic film. It seems to have inevitably brought tears to families as they watched it in movie theatres or when replayed on TV.[20]

Documented songs remain the jokō’s most powerful voice in their mix of fierce pride and steely nerve. One most resonant today lionizes a silk worker in Nagano named Iwataru Kikusa for being a “fighter against male oppressors met every day within the factory.”[21] When attacked in 1907 when returning back to her dormitory, she seized the balls of her assailant so forcefully that he revealed his face, leading to his arrest. The man turned out to be a wanted murderer. Two verses of the song ran:

Iwataru Kikusa is a shining

Model of a factory girl.

Let’s wrench the balls

Of the hateful men!

Who dares to say that

Factory girls are weak?

Factory girls are the

Only ones who create wealth.[22]

The term jokō aishi (“sorry history of factory girls”) from the 1925 exposé is now used as a title for books about the exploitation of textile workers in Southeast Asia and China.

Concluding Remarks

The visual and textual evidence from these nishiki-e allows us a few glimpses of very different settings for women’s labor (in our broad definition of labor). Because of the blur between imagination and reality in these prints, they provide a skewed view. They express the aspirations of the period more than lived reality. We have considered a set of complementary questions: What was the social meaning of what they wore? Who made them? Where were they made? Questioning their clothing for what is fanciful in these woodcuts allows us to interrogate the degree of truth portrayed. For, as we learn when we read actual accounts, most did not have such a happy, easy lifestyle, nor did many so always contentedly conform to social expectations in this picture-pretty way. Many of the actual daughters of Meiji were made of much tougher stuff than it may appear.

Notes

In researching the images in this essay, I am especially grateful for the input of Ota Shōko and Karen Mack among others. I thank Tristan Grunow and Christine Guth for their editing suggestions that helped smooth out the prose. Any remaining errors and infelicities are solely my own.

[1] The phrase is from Raymond Williams, “Advertising: The Magic System” in Williams, Raymond, Culture and Materialism, 175-90. London: Verso, 2005.

[2] Often the characters were reversed to kōjo 工女.

[3] For good description of one of the networks, see Kären Wigen, The Making of a Japanese Periphery, 1750-1920. Berkeley: U of C Press, 1995.

[4] Liza Dalby, Geisha Berkeley: U of C Press, 1983, provides a book-length survey with only a few hasty conclusions. Mikiso Hane, in his chapter“Poverty and Prostitution” in Peasants, Rebels, & Outcasts: The Underside of Modern Japan (Pantheon Books, 1982) gives a picture of the darker reality. For a fascinating example, see Sone Hiromi (Suzanne O’Brien translator) “Conceptions of Geisha: A Case Study of the City of Miyazu,” in Gender and Japanese History, vol.1 (Osaka University Press, 1999).

[5] Mio Wakita, Staging Desires: Japanese Femininity in Kusakbe Kimbei’s Nineteenth Century Souvenir Photography. Berlin: Reimer, 2013.

[6] My translation.

[7] Julia Meech-Pekarik, pp. 128-130 and passim The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization. New York: Weatherhill, 1986.

[8] For an excellent essay that explicates on representation of women sewing in the Western manner during this time, see Alison Miller, “A Note on Adachi Ginkō’s Picture of Noble Ladies Sewing: Women and Nationalism in a Meiji Print” in Spencer Museum of Art: July 1, 2006- June 30, 2007, 42-49.

[9]See Meech-Pekarik, 164, on another similar print with a pianist.

[10] Bacon’s book remains a testament to the proud strength the rise of a new cosmopolitan elite. Yet, Bacon, as was typical of her class, wrote about women who worked at being members of the leisure class and was blind to the plight of the vast majority of working Japanese women. For a contemporary source that reports on the more impoverished, see Sydney Gulick, Working Women of Japan (1915).

[11] The best book-length survey of the shifts in kimono fashions and attitudes since the late nineteenth century is Terry Satsuki Milhaupt, Kimono: A Modern History. London: Reaktion Books, 2014.

[12] Hane, p 41.

[13] See E. Patricia Tsurumi, Factory Girls: Women in the Thread Mills of Meiji Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990; Janet Hunter, Women and the Labour Market in Japan’s Industrialising Economy: The textile industry before the Pacific War. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

[14] Tsurumi, p. 92.

[15] Tsurumi strongly makes this argument.

[16] Wada Ei, Tomioka Nikki, 1931 with many reprints. This has recently been translated by Alan Lewinski and Maiko Lewinski as Ei Wada, Tomioka Diary. Nagano: Shinshu Educational Publishing Co, 2016.

[17] Hane.

[18] The subtitle “Yet to be heard?” refers to the title of an article written by the late formidable scholar of University of Victoria, E. Patricia Tsurumi, who translated the stories and songs of these down-trodden factory women into English.

[19] See “Changing Consciousness: Takai Toshio’s My Own Sad History of Female Textile Workers (Watashi no jokō aishi) in Ronald P. Loftus, Telling Lives: Women’s Self-Writing in Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004, 82-131.

[20] From my personal interviews with a number of Japanese people.

[21] Tsurumi, 197.

[22] Idem. Translated from Yamamoto Shigemi’s Aa nomugi tōge.

About the Author

Miriam Wattles is Associate Professor in the Department of Art and Architecture, University of California, Santa Barbara. She has worked on a range of topics in Japanese visual culture from the Edo through the early Shōwa periods. Her present book project concerns the little-known transition from giga to manga from 1870-1930. The gendered history of textiles and garments in Japan during the long twentieth century is a new scholarly interest of hers.

Miriam Wattles is Associate Professor in the Department of Art and Architecture, University of California, Santa Barbara. She has worked on a range of topics in Japanese visual culture from the Edo through the early Shōwa periods. Her present book project concerns the little-known transition from giga to manga from 1870-1930. The gendered history of textiles and garments in Japan during the long twentieth century is a new scholarly interest of hers.

Faculty of Art

Faculty of Art