Eiji Okawa

University of Victoria

On Alexander Street in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside stands Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall. The school has served as a pillar of the Nikkei community since very early in the twentieth century. [1] The current premises include a section built in 1928, now designated by the city as a heritage site. The historic building witnessed dramatic changes over time, not least of which being the destruction of the Japanese-Canadian community by wartime policies. Until early in 1942, this area of town thrived as a vibrant Nikkei neighbourhood. The Canadian state didn’t just expel “persons of the Japanese race” from the coast. It also sold properties they left behind without their consent. The school was a notable exception. Its board members navigated political pressures in the 1940s to keep the building in their hands.

The school is neither public nor private but communal (kyōritsu, meaning “sustained together,” is how it styled itself in prewar times). Not supported by government funding, maintaining the school itself was a formidable task. In the 1920s, the community grew, and the original school opened in 1906 became inadequate to accommodate increasing enrolment.

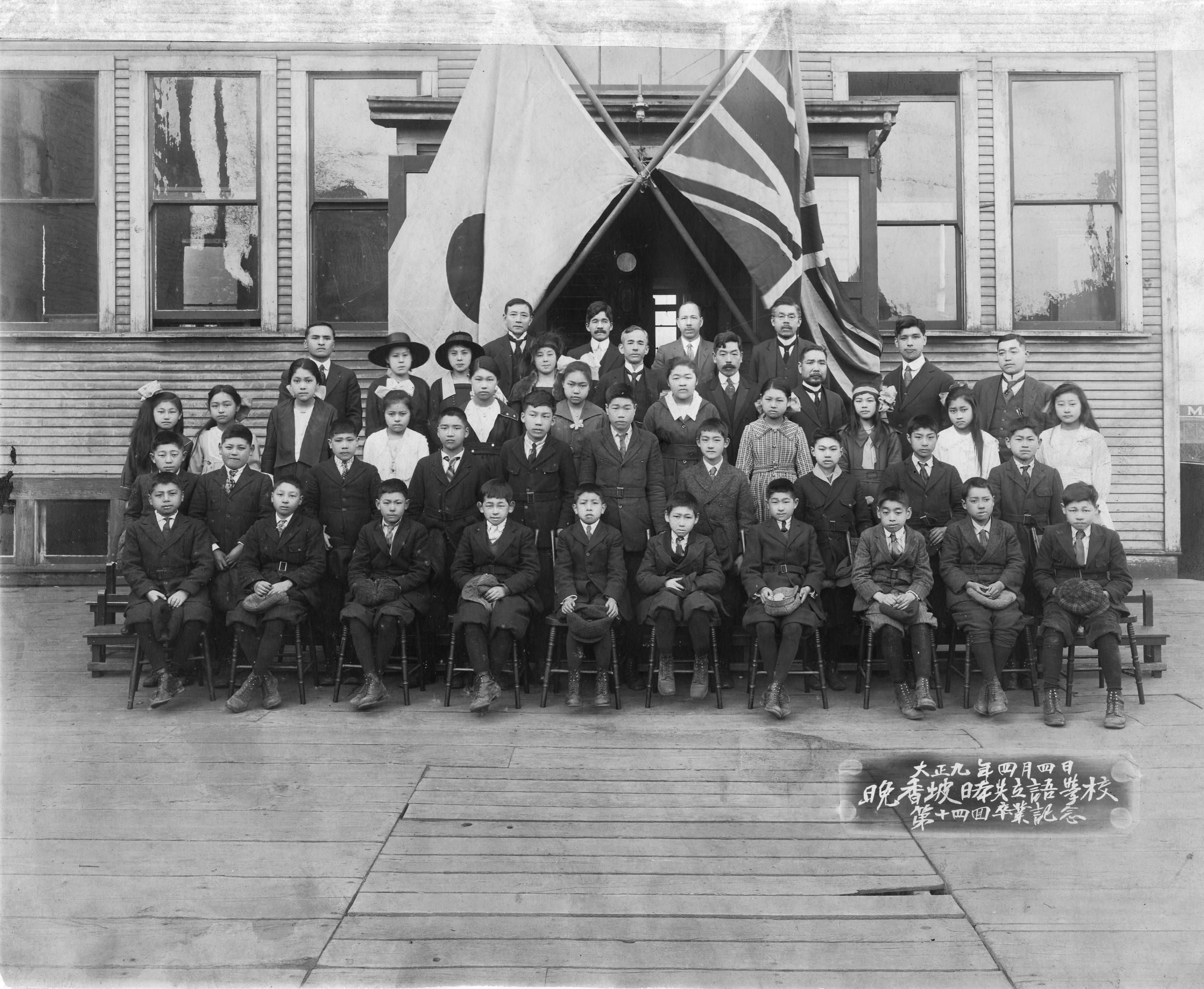

Fig. 2: The “old” school at 439 Alexander Street operated from 1906 to Monday, December 8, 1941, a day after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor. On that day, the RCMP phoned the school to order closure of all Japanese language schools in the province. Classes were dismissed by afternoon. Later in 1947, this building was sold under the Canadian government policy to sell properties owned by Japanese Canadians after they were physically removed from the area. Note that the sale occurred two years after the end of war and had nothing to do with security threat, the slogan under which Japanese Canadians were confined in internment. Indeed, persons of Japanese backgrounds were prohibited from returning to the coast until 1949, as anti-Japanese sentiment ran high in British Columbia. See endnote for representative literature on Japanese-Canadian history with emphasis on discriminatory policies, internment, dispossession, and exile. [2] Source: University of British Columbia Library, Rare Books are Special Collections, Japanese Canadian Research Collection, JCPC_25_058. (Click to enlarge, or visit source here).

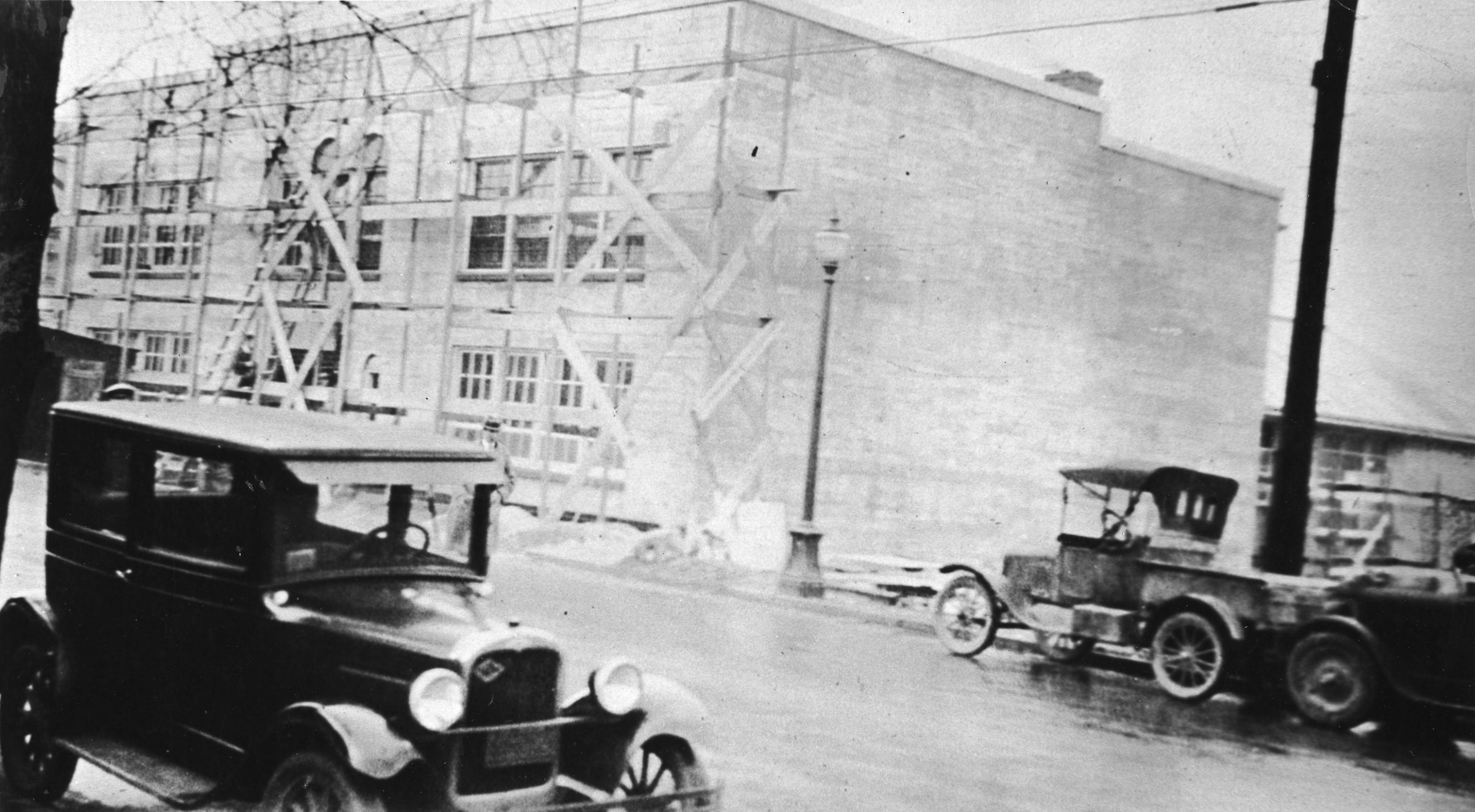

Photographs show the construction of the 1928 building underway roughly ninety years ago.

Fig. 4: Nikkei women and a man posing for a photo in front of a scaffolding. Woman to our left is Hanako Sato, and man on right in Tsutae, her husband. The women in the middle may have been teachers or members of the school’s Mothers and Sisters Association (boshikai), which played critical roles in running the affairs of the school. Canadian Centennial Project Fonds, NNM 2010.23.2.4.224 (Click to enlarge).

Fig. 5: This photo taken on January 19, 1928 shows the building close to completion. Canadian Centennial Project Fonds, NNM 2010.23.2.4.226 (Click to enlarge).

Tsutae Sato, who served as principal from 1921 to 1966, has said the building was the crystallization of the heart and soul of every member of his community and the biggest accomplishment of his generation of Issei immigrants. [4] As it is the case with any group of people, there were diverse interests and agendas creating fissures and tensions within the Nikkei community of the day. But differences were put aside to unite under the common goal of the education of heirs in the Japanese language.

Why was Japanese school so important and what roles did language education play in the community?

Caveats

A couple of historical factors need to be fleshed out. The first is prewar Canada’s approach to difference and diversity. Living in the late 2010s, we are aware that Canada is a country avowing to stand by the values of inclusion and diversity, even as entrenched prejudice and discrimination remain to marginalize people based on their race and social backgrounds. Canadian multiculturalism is a postwar construction that can’t be taken for granted. Prewar Canada was diverse and plural, too, but it was a society organized by codified and pervasive forms of discrimination and oppression. As white settlers dominated political processes, they took land away from First Peoples, crushing their communities, maiming their intricate relations to the environment and resources, and subjecting them to the laws of the settler regime that undermined their rights and interests. Unfair restrictions were imposed upon the entry of migrants from Asia to safeguard white interests, and as a general rule, people of colour were barred from political participation with the denial of the franchise. At the pinnacle of the racialized order were the British, but arguably, there were strands of ideas akin to multiculturalism. Canadian society was a “mosaic,” it was said. But that really meant diversity among peoples of European descent. [5]

Second, the way Japanese migrants expressed themselves in the prewar era differs from how their descendants do in our time. Issei wrote and talked in Japanese, and concepts and ideas they evoked were rooted in the cultural norms of Japanese modernity. To generalize, whereas Japanese Canadians since the latter half of twentieth century have come to assert themselves primarily as Canadians with Japanese background, their predecessors, especially Issei, tended to think of themselves as Japanese members of a plural Canadian society. They sought integration into the social fabric of their adoptive country without compromising their Japaneseness. One specialist of Japanese-American history observes that in prewar “Japanese America,” the sense of belonging was not singular or exclusive but “eclectic.” [6] This characterization applies to the Nikkei community north of the border. Rigid ideas about the nation prevent us from coming to terms with their identities and subjective positions.

The remainder of this essay sketches out fragments of prewar Japanese-Canadian expressions of identity, drawing on precious historical records held in the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre in Burnaby and the UBC Library’s Japanese Canadian Research Collection in Rare Books and Special Collections. Note that excerpts of historical texts appearing in the paragraphs to follow were translated by the author. [7]

Language Education

According to newsletters circulated by the Alexander Street school, the aim of language education was not simply to develop linguistic competency but to cultivate Japanese values and even “spirit” (nihon seishin). The emphasis on ethical cultivation was modeled on Confucian teachings and dovetailed with the educational curriculum developed in the Meiji period. From postwar perspectives, prewar moral education (shūshin) is easily condemned as an ideological machination of imperial governance. But the community’s approach to education should be considered in light of cultural conceptions and worldviews entwined with it. Nikkei educators and parents tended to presume their language embodied virtues and values they believed to be universal. Therefore, learning was naturally ethical and didactic. Language, in other words, was more than a means for communication. It was a hallowed repository of cultural capitals of the homeland, to be bequeathed to descendants during formative stages of their personhood and character.

Fig. 6: Classroom of Japanese language school, ca. 1920s. This is the original school located at 439 Alexander Street. Teacher standing on the side is Tsutae Sato. Canadian Centennial Project Fonds, NNM 2010.23.2.4.257 (Click to enlarge).

Fig. 7: Students enjoying ice cream with Sato-sensei and another teacher during a picnic outing, ca. 1920s. Canadian Centennial Project Fonds, NNM 2010.23.2.4.220 (Click to enlarge).

To be sure, since the 1920s, as migrants increasingly considered Canada as the country of their permanent residence rather than a temporary job site, the dominant view of the community regarded Canadian public schools as the primary educational institutions for Canadian-born Nisei (second generation). Language schools only provided supplementary learnings, but in so doing, they were to nurture students’ growth into good Canadian citizens. That is, language schools were intended to bolster Nisei’s Canadianization. Issei parents were anxious about the future of their children in Canada, and whether or not they would prevail against racist exclusion loomed large in community discussions. [8] Nisei’s performance in Canadian schools served as a barometer for contemplating their future prospects. Indeed, with their diligence and work ethic, many Nisei excelled in their studies and showed they had the stuff to succeed in Canadian society.

Yet parents and teachers insisted on Japanese values. An essay titled “Things We Want to Nurture in the Nisei” (Kongo dainisei ni kanyō shitai mono), featured in the newsletter’s December 1936 issue, expounds on four cardinal “Japanese” virtues: 1) indomitable spirit (futō no seishin), 2) the heart of pride and self-respect (hokori no kokoro), 3) the spirit of reverence and gratitude (kei/uyamai no seishin, kan’on no seishin), and 4) the spirit of service (hōshi no seishin). Emphasised by teachers of the language school, these virtues were understood to empower the Nisei to overcome exclusion and facilitate their integration into Canadian society.

This mentality is reflected in the following composition written by Kikuchi Toshio, a student at Japanese Language School in New Westminster. His piece was featured in July 31, 1934 issue of Vancouver’s Nikkei newspaper, Tairiku Nippō (Continental Daily News).

“My Thoughts on the Future as a Nisei: Where are We Headed?

Born in Canada in British territory, I am Nisei and hence differ from my parents. Though I am a Nisei myself, I feel that Nisei in general suffer from a certain lack, namely of Japanese learning [Nihon-gaku]. Nisei tends to be fluent in English but many of them are clueless when it comes to Japanese learning. Therefore, they are looked down upon by the Issei.

Some Nisei say “I’m a Canadian [kanada-jin] so there is no need for me to take up Japanese learning.” Of course, as Canadians we should be granted the right to vote but that is not the case. In newspapers I often read about the uncertain future of the Nisei. If we go around thinking like hakujin [whites] kids, we will doubtless end up without jobs [due to discrimination in employment]. Now, therefore, we must rid ourselves of the shortcomings of Japanese and embrace their merits and strengths. That is, we ought to draw on Japanese strengths as well as hakujin’s and devote ourselves to our occupations. We must pursue our paths while never forgetting the homeland. Unlike us, the Issei could not speak English well thus could not take part in hakujin society. But our era is on the horizon. We are fluent in English and Japanese. The only thing we lack is the spirit of effort (doryoku).

With the beautiful Japanese spirit of effort, I am determined to drive myself into hakujin society. I will prevail over any obstacle along the way by wringing every ounce of effort from my heart and blood. We are the foundation for the Sansei [third generation]. If we fall now the fate of the Sansei would be jeopardised. I will be a fine Canadian no hakujin can laugh at.

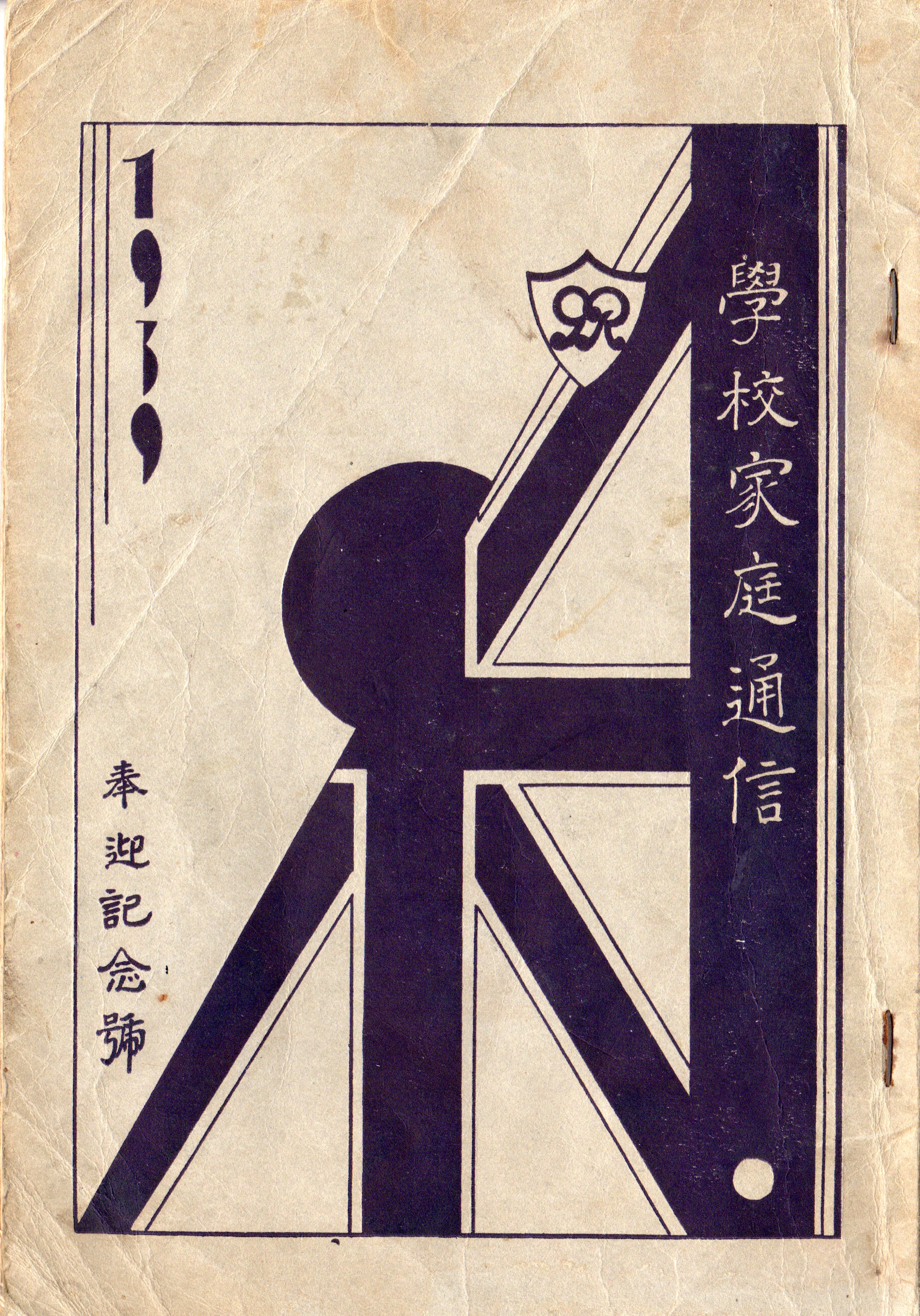

Fig. 8: An image of the Rising Sun fusing with the Union Jack on the cover of the Alexander School newsletter (Gakkō katei tsūshin)’s special issue to commemorate the Canadian tour of King George and Queen Elizabeth in June, 1939. Used with permission from Nancy Morishita’s private collection (Click to enlarge).

Toshio’s piece alludes to a complex dynamic within the community. Many Nisei apparently resisted or rejected Japanese learning, imposed as it was by their parents. But his writing conveys a visceral sense of yearning for a full membership in the Canadian nation, juxtaposing the reality of systemic exclusion and marginalization. Lacking political representation and having employment prospects diminished by racial discrimination, Toshio believed there was no way for the Nisei to prosper in Canada if they simply went about their lives like white youths. For Toshio, this was not merely a matter of Nisei’s individual lives; rather, the fate of the community rested on their shoulders. The Nisei, he believed, bore the duty to lift the community from marginality. Fortifying his willpower with Japanese spirit, Toshio was determined never to give up in his pursuit of becoming a “fine Canadian” (rippa na kanada-jin).

No doubt, Toshio’s attitude was a result of his socialization and upbringing. His was the sort of argument the Issei wanted to hear from the Nisei. It also reminisces the concept of the nation as a “melting-pot,” which combined and reduced attributes of numerous groups to forge a unified peoplehood. All the same, this kind of hybrid imagining of the nation was not entirely a diasporic construct. Japanese statesmen, too, admonished the Nisei to commit to their country, not Japan. As former Minister of Colonial Affairs and governor of Tokyo Nagata Hidejirō (1876-1943) told Sato, education of Nisei must focus on their growth into “good Canadians” (zenryō naru kanada-jin). [9] He used a parable of marriage within the patriarchal mores of Japanese modernity to argue that, like a wife who commits herself to the prosperity of her husband’s family, the Nisei must devote themselves to their adoptive nation. The wife’s donning of a white kimono during the wedding symbolized her “death” as a member of her natal family. Likewise, the Nisei must have no question about their allegiance. Yet, he argued for the importance of nurturing the Nisei with Japanese morality, for that was the basis for the progress of the Japanese nation (nihon minzoku no hatten). Here, Nagata’s nationalism is not exclusive or antagonistic to Canada. He placed the Nisei in the body politic of the Canadian state, just as he regarded them members of the Japanese ethnic community extending across the Pacific. Nisei’s Japaneseness, vitalized by moralistic education, boosted their capacity to contribute to both.

Indeed, a sense of dual belonging was the orthodox way the community understood and situated itself in Canada, and this was related to the notion that it occupied a space linked with the British empire, Japan’s ally in the contentious arena of global politics.

Performing Collective Identity

The hybrid identity was not only debated or discussed but also enacted in public spaces.

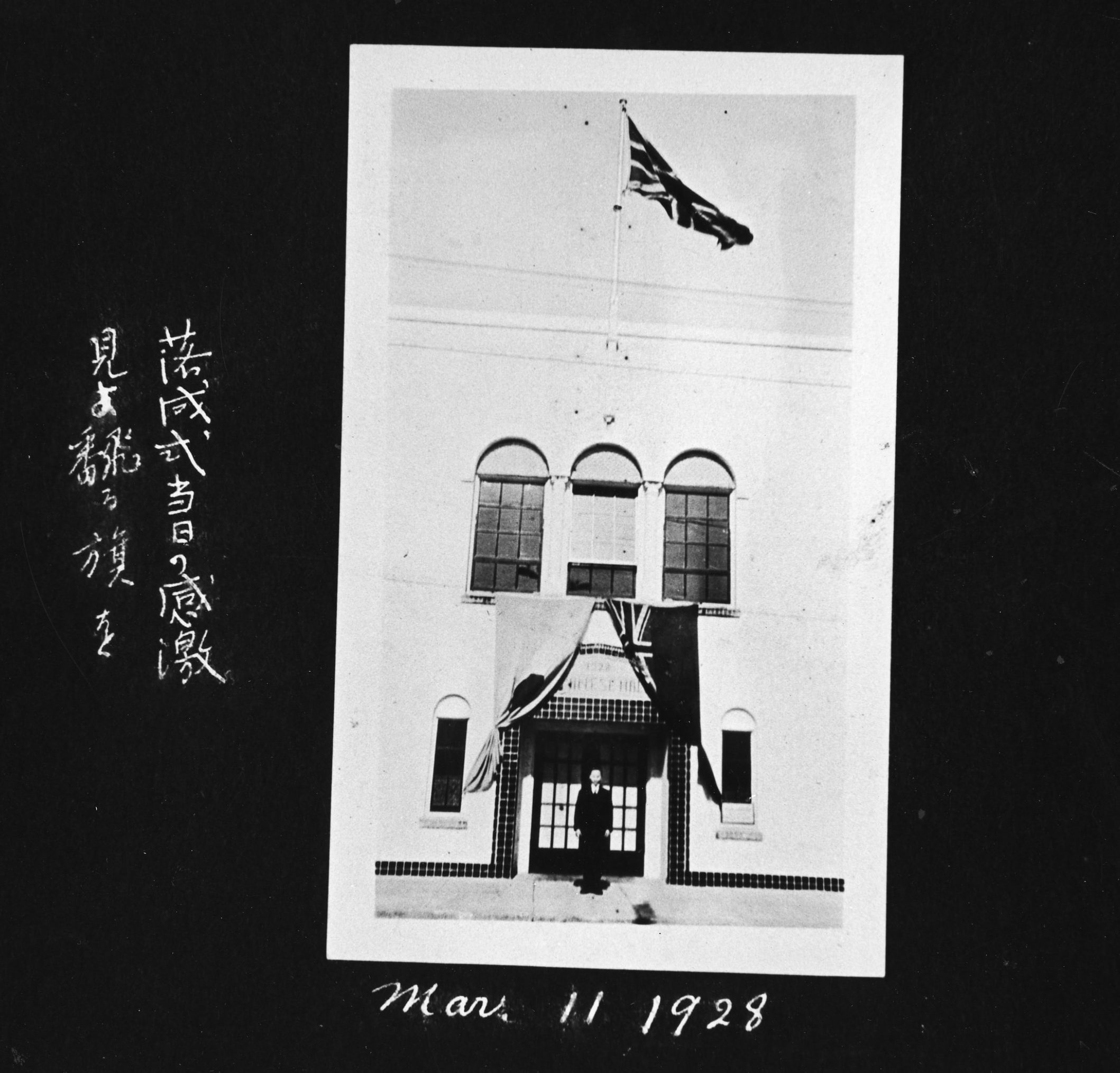

Fig. 9: Canadian Centennial Project Fonds, NNM 2010.23.2.4.223. This image is a scan of Tsutae’s photo album, housed today in Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto. Japanese caption says, “jubilation of the opening day, look at the soaring flag!” (Click to enlarge).

Taken on the day of the opening ceremony of the 1928 school building, the photograph shows the Rising Sun beside Red Ensign which was the Canadian flag at the time, draped over the main entrance while the Union Jack flies above on the flagpole. The flags befit an institution dedicated to the transmission of Japanese language and culture to Canadian-born children to facilitate their growth as good Canadians.

The flags were also dramatically displayed during graduation ceremonies at the school as well as communal events and gatherings.

The last photo shows a large crowd of people in the front yard of the school, gathered for an event involving a speech or discussion. Participants are predominantly men in formal attire. Possibly, this was an assembly of the Canadian Japanese Association (Kanada Nihonjinkai) an influential association of elite men that coordinated and organized communal affairs. [10]

The school served as a forum for associational lives of the community. The new building included the Japanese Hall used by community groups to hold various events and assemblies. Below is a 1940 photograph of the fifth annual convention of the Japanese Canadian Citizens League, a Nisei group that lobbied Ottawa to grant them full civil rights.

The school was also the venue for monthly and annual meetings of Japanese Women’s Association (Nippon Fujinkai). Here is a photo from the association’s tenth anniversay event, held in 1918 at the language school. [11]

A dramatic display of prewar Japanese-Canadian identity was occasioned by the Royal Tour of Canada by King Gorge and Queen Elizabeth in 1939. Japanese Canadians in the Fraser Valley set up an arch in New Westminster to welcome the sovereigns. This followed from the earlier practice of erecting arches during royal visits both from Japan and Britain.

Fig. 15: View of gate and decorations at the foot of Granville Street in honor of visit of Prince Fushimi to Vancouver in 1907. Source: University of British Columbia Library, Rare Books are Special Collections, Japanese Canadian Research Collection, JCPC_38_001 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here.)

In 1939, however, girls and women dressed in Japanese kimono and filled a section of the city’s street, waiting for the sovereign couple. Tairiku Nippō reported on the extraordinary scene in New Westminster in its June 3rd issue.

In Vancouver, Nikkei people organized a reception in a similar style as they mingled with other Canadians. Rows of girls and young women in kimono waved the Union Jack as the Royal entourage came their way.

They also gathered at the school.

Rather than waiting passively to see the King and Queen, the community took part in the great public spectacle, parading the streets with special floats. The photo of the float bearing the banner “Japanese Community” was taken in front of the Tamura building, situated at the corner of Powell and Dunlevy Streets in the heart of Vancouver’s Nikkei neighbourhood, also known as “Japan town.” On the spectacular float decorated with the Crown, a Nikkei girl and boy impersonated the Royal couple. Sakura (cherry blossoms), Shinto torii (arches), and girls in kimono symbolized the heritage of the community.

A photo from the back indicates the dedication of the torii to the King and Queen, thus engraved with letters G and E.

Deployment of kimono and girls was strategically planned and coordinated by the Canadian Japanese Association in liaison with the Mothers and Sisters Association of the Alexander Street school. The community had always faced harsh discrimination and exclusion by mainstream Canadians, but it confronted heightening animosity in the 1930s fueled by Japan’s invasion of China and its relentless fascist colonial pursuits. Canadian public opinion linked and conflated the Japanese state and military with Canadian citizens and residents of Japanese heritage, therefore, anxiety toward Japan in global politics was directed toward Nikkei residents. The community tried to facilitate mutual understanding but with little success, and Japan’s increasing alienation from the international community didn’t help. Anti-Japanese politicians incited fear among the mass and argued for the “inassimilability” of persons with Japanese blood in their veins. In such a context, young women in kimono must have been perfect exemplars of Japan’s cultural refinement, safe and benign as well as fitting with the romanticized imaginings of Japanese aesthetics.

Rupture in Identity

After Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the thrust of exclusion prevailed. Nikkei people were uprooted from their homes and communities as the government designated a hundred-mile corridor along the coast as a “protected area” where they could not remain or enter. They were confined in internment in the name of “national security,” then dispersed across the country as BC politicians adamantly opposed their return to the coast even after the war ended. Homes, businesses, and other properties they left behind were not only stolen and vandalized but also forcibly sold and liquidated by the state.

Ramifications of these events were far-reaching. In the postwar era, Nisei intelligentsia claimed that prewar language education had stifled the Nisei from becoming authentic Canadians. [12]Partly this has to do with a generation gap one may observe in any diasporic community, as well as the general ideological force of assimilation. For this community, however, postwar ambivalence toward Japaneseness was also a response to political violence on the grounds of race. With the trauma of the 1940s, Japanese Canadians felt compelled to dissociate themselves from cultural baggage from Japan and avoid anything that set them apart from other Canadians, for their difference stirred agitation of the mainstream and hindered their membership in the Canadian nation.

Multiculturalism in Canada emerged in the aftermaths of the merciless denial of Japanese-Canadian rights. Tolerance, inclusion, and respect for difference are among the core tenets of Canadian multiculturalism, which is also couched upon the logic of the equality of the individual regardless of one’s racial, religious, cultural, or social backgrounds. Looking back to prewar times, Canada was a society organized by the inverse of these values.[13] Confined to the fringes of Canadian society, Japanese Canadians empowered themselves with Japanese culture and values and claimed their space in what they regarded as the multi-nations-state of Canada.

How do our nationalisms and ideas about the nation influence the way we understand and tell Japanese-Canadian history? What do Nikkei historical experiences tell us about the complexity of the past and the evolving terrains of Canada’s diverse and discriminatory society?

Endnotes:

[1] Nikkei refers to people of Japanese heritage. In this essay, this term is used to refer to Nikkei people in Canada.

[2] For works on Japanese-Canadian history with a focus on racist politics and wartime policies, see Ken Adachi, The Enemy that Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1976); Ann Gomer Sunahara, The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War (Toronto: J. Lorimer, 1981); Patricia E. Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1989); Roy, The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941-67 (Vancouver: UBC press, 2007); and Roy, J. L. Granatsein, Masako Iino, and Hiroko Takamura, Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese during the Second World War (Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto press, 1990). Greg Robinson provides a comparative analysis of Canadian and American treatment of persons of Japanese heritage during the Second World War in his A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009). For essays on Nikkei histories in Canada and America, see Louis Fiset and Gail M. Nomura, eds., Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century (Seattle: Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest in association with University of Washington Press, 2005).

Some of these historiographies were closely related to the postwar activist movement to seek formal apology and redress from the Canadian government for its wartime mistreatment of citizens of Japanese lineage. Redress, achieved in 1988 with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney offering a formal apology in the House of Commons, was a momentous event in Canadian history. For developments of the redress movement, see Roy Miki and Cassandra Kobayashi, Justice in Our Time: The Japanese Canadian Redress Settlement (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1991); Roy Miki, Redress: Inside the Japanese Canadian Call for Justice (Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 2004). Tatsuo Kage discusses the exile of Japanese Canadians in 1946 with rich oral historical accounts in his Uprooted Again: Japanese Canadians Move to Japan after World War II, trans. Kathleen Chisato Merken (Victoria, BC: Ti-Jean press, 2012, orig.pub. in Japanese (Akashi shoten, 1998).

The oral historical approach has been immensely important in recent discussion of Japanese-Canadian history. For studies employing oral historical methods, see Pamela Sugiman, “Memories of Internment: Narrating Japanese Canadian Women’s Life Stories,” The Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie 29/3 (Summer 2004), 359-88; Sugiman, “’Life is Sweet’: Vulnerability and Composure in the Wartime Narratives of Japanese Canadians,” Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d’Études canadiennes 43/1 (Winter 2009), 186-218; and Mona Oikawa, Cartographies of Violence: Japanese Canadian Women, Memory, and the Subjects of the Internment (Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto press, 2012).

Important contributions to Japanese-Canadian history by community historians include Roy Ito, We Went to War (Stittsville, ON: Canada’s Wings, 1984); Ito, Stories of My People (Hamilton, ON: S-20 and Nisei Veterans Association, 1994); and Masako Fukawa with Stanley Fukawa and Nikkei Fishermen’s History Book Committee, Spirit of the Nikkei Fleet: BC’s Japanese Canadian Fishermen (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Pub., 2009).

The dispossession of Japanese Canadian is being comprehensively examined and analyzed by researchers of Landscapes of Injustice, a collaborative research project of which the author is a part as a postdoctoral researcher. Recent works by Landscapes researchers include Jordan Stanger-Ross and Landscapes of Injustice Research Collective, “Suspect Properties: The Vancouver Origins of the Forced Sale of Japanese-Canadian-Owned Property, WWII,” Journal of Planning History 15/4 (2016), 271-89; Stanger-Ross and Nicholas Blomley, “’My Land is Worth a Million Dollars’: How Japanese Canadians Contested Their Dispossession in the 1940s,” Law and History Review 35/3 (2017), 711-751; Eric M. Adams, Jordan Stanger-Ross, and Landscapes of Injustice Research Collective, “Promises of Law: The Unlawful Dispossession of Japanese Canadians,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 54/3 (2017), 687-740; Stanger-Ross and Sugiman, eds., Witness to Loss: Race, Culpability, and Memory in the Dispossession of Japanese Canadians (Montreal and Kingston; London; Chicago: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017); and articles in the Journal of American Ethnic History special issue with Landscapes of Injustice forthcoming in summer of 2018. In addition to academic studies, Landscapes is developing teacher resources, museum exhibits, and public history as well as an archival website to share research findings with public audiences. Witness to Loss also has a website providing compelling records of a Japanese Canadian man involved in the Canadian policy to dispossess people in his community. These are merely a selective sample of the wealth of works and literatures on Japanese Canadian history.

[3] Tsutae Sato, ed. Bankūbā nihon kyōritsu gogakkō enkakushi, History of Japanese Language School (Vancouver: Bankūbā nihon kyōritsu gogakkō ijikai, 1954), 174.

[4] Sato, Enkakushi, 177.

[5] As John Murray Gibbon put it in his 1938 book, Canadian Mosaic: The Making of a Northern Nation (McLelland & Stewart ltd, Toronto), Canadians are “made up of European racial groups, the members of which are only beginning to get acquainted with each other, and have not yet been blended into one type. Possibly, in another two hundred years, Canadians may be fused together and standardized so that you can recognize them anywhere in a crowd…” (vii).

[6] Eiichiro Azuma, Between Two Empires: Race, History and Transnationalism in Japanese America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[7] This collection boasts exceptionally rich historical records of Issei from the early to mid twentieth century. Importantly, this collection came into existence as a result of an urgent call in 1971 by long-time Alexander Street school teacher Tsutae Sato, who we shall touch on in this essay, to save Issei records from oblivion as Issei entered twilight years and generation changed. Prior to that, the records were held by Japanese-Canadian individuals and families some of whom played vital roles in the community’s economic, cultural, and religious lives. Mitsuru Shinpo, a UBC-trained sociologist who oversaw the creation of the collection recounts the donation of materials from community in his monograph on Japanese-Canadian history, Ishi o mote owaruru gotoku [As if Being Chased with a Stone] (Tokyo: Ochanomizu shobō, 1996, orig. pub. 1975). For an inventory of records in UBC RBSC’s Japanese Canadian Research Collection, see http://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/uploads/r/university-of-british-columbia-library-rare-books-and-special-collections/6/7/67725/japanese_canadian_research_collection.pdf.

[8] Gakkō katei tsūshin, vol.35 (Dec. 1938), 2. This is the school’s prewar newsletter. I referenced the copies in Tsutae and Hanako Sato Fonds housed in the Nikkei National Museum.

[9] On this, see texts concerning Nisei’s education in Canada compiled in 1926 and 1927 by Canadian Japanese Association, https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/meiji150/items/1.0364381, and https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/meiji150/items/1.0364337#p0z-7r0f: Copies of these texts are found in Yasutaro Yamaga Fonds in UBC library’s Rare Books and Special Collections. For inventory of materials in Yasutaro Yamaga Fonds, see http://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/index.php/yasutaro-yamaga-fonds.

[10] For an English account of activities of this association in the prewar era, see Adachi, 123-27.

[11] According to Nakayama Jinshirō, the Japanese Women’s Association was originally established in Vancouver in 1904. However, 1908 was an watershed for the association, which passed legislations including a stipulation to use the school for its meetings and assemblies. Anniversary here likely refers to the years passed since then. Nakayama Jinshirō, Kanada dōhō hatten taikan, zen [Encyclopedia of the Progress of Japanese in Canada] (1921), 1691-92, in Sasaki Toshiji and Tsuneharu Gonnami, eds. Kanada iminshi shiryō, vol. 8. Tokyo: Fuji Shuppan, 2000. For a brief account of Japanese Women’s Associations in prewar Canada, see my “Associational Lives of Women in Prewar Japanese-Canadian Community” in UBC Meiji at 150 Digital Teaching Resource.

[12] See Adachi, 127-28.

[13] This statement borrows from Mary Elizabeth Berry’s analysis of the public sphere in prewar Japan in her article, “Public Life in Authoritarian Japan,” Daedalus 127, no. 3 (1998): 137.

About the author

Eiji Okawa is a social historian specializing in medieval and early modern Japan as well as Japanese diaspora in early to mid twentieth century Canada. He is interested in religious and social institutions, and how people relate to cultural landscapes and organize their society by managing or overcoming conflicts and tensions. He completed his doctoral degree in Japanese history at the University of British Columbia in 2016. Currently, he is a postdoctoral fellow with Landscapes of Injustice as well as University of Victoria’s history department. Landscapes is a collaborative project on the dispossession of Japanese-Canadian properties by the state during the 1940s.

Eiji Okawa is a social historian specializing in medieval and early modern Japan as well as Japanese diaspora in early to mid twentieth century Canada. He is interested in religious and social institutions, and how people relate to cultural landscapes and organize their society by managing or overcoming conflicts and tensions. He completed his doctoral degree in Japanese history at the University of British Columbia in 2016. Currently, he is a postdoctoral fellow with Landscapes of Injustice as well as University of Victoria’s history department. Landscapes is a collaborative project on the dispossession of Japanese-Canadian properties by the state during the 1940s.

Faculty of Art

Faculty of Art