Naoko Kato

University of British Columbia

UBC Library’s Meiji at 150 collection consists of woodblock prints, photographs, as well as hand-painted manuscripts. It compliments the Japanese Maps of the Tokugawa Era collection, which is a fully digitized collection that is used extensively in Japanese Literature, Art History, and History classes. The Meiji at 150 collection provides us with a unique opportunity to consider how we teach and learn about Meiji Japan, particularly in a North American context. This is because many of the items pertaining to the Meiji era reveal much about Japan’s relationship to Canada. For example, we have photographs from Taishō and Meiji, taken in Japan, by a Canadian missionary. We also have Japanese-Canadian photographs taken during the anti-Asian 1907 race riots in Vancouver, as well as travel posters advertising travel to Japan by the Canadian Pacific Railway. In addition, we have woodblock prints that were printed in Japan, that depict Japan’s westernization and modernization. Though all of these materials were produced in the Meiji era, they were created for a wide range of reasons, for difference audiences. The Meiji at 150 collection makes it possible for students to examine these vastly diverse items together, and re-examine how Japanese and Canadian histories intersected during the Meiji era. For the purpose of this essay, I have divided the Meiji at 150 collection into three categories; Japan’s self depiction, Japan seen from Canada, and Japanese-Canadian, according to the three major perspectives from which the collection can be potentially examined.

Figure 1. Ikkei, “Kaiunbashi Kawaseza no zu.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L3:5 (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

Japan’s Self-Depiction – woodblock prints of modern Japan

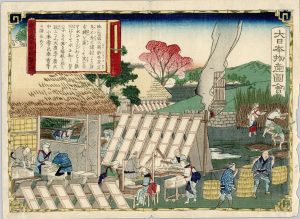

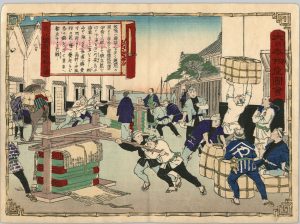

Kaika-e (civilization and modernization pictures), feature symbols of modernization such as bridges, railroads, Western-style buildings (see Tristan Grunow’s essay). In addition, ukiyo-e artists often consciously included Japanese motifs such as Mt. Fuji in the background with cherry blossom trees in the foreground, to emphasize Japan as a modern nation. Fig. 1 is a typical kaika-e, which highlights the financial district of Kaiunbashi, with the first Japanese national bank (daiichi kokuritsu ginkō). This building was financed by entrepreneur Shibusawa Eiichi, and was also called Mitsui-gumi building because of Mitsui family’s funding. These woodblock prints aim to demonstrate Japan’s strength of possessing both cultural traditions of “old” Japan, combined with Western technologies and knowledge. Woodblock prints in the Meiji era increasing became modes of historical recording and a means to inform the public on contemporary events.[1] Fig. 2, from Dai nihon bussan zue (Products of Greater Japan), is one of a series of 120 woodblock prints depicting the economies and industries in Japan from each region, published by Ōkura Magobē. Japan held its inaugural National Industrial Exhibition in 1877, in Tokyo, and Hiroshige III published the series Products of Greater Japan to coincide with the exhibition.[2] The exhibition’s aim was to survey domestic products through collection, display, research, examination, and ranking products, which was thought to lead to the promotion of local industries.[3] This went hand in hand with the main objectives of the Meiji government’s “shokusan kōgyō seisaku” (industrial development policy), which was to “collect items from all over Japan, to categorize them, and to exhibit them to make known to the populace.”[4] Not only were these prints used to highlight each region’s industries, but also acted as a medium to transfer knowledge on technological advancements.

Figure 2. Hiroshige III. “Echizen no kuni hōsho shisei no zu.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L2:12. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

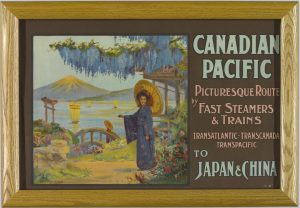

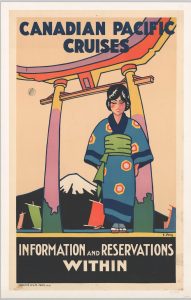

Japan Seen from Canada

UBC Library’s collection includes the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, which contains visual materials such as travel posters published by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. The primary target audiences for, as well as the designers of these posters were British and American.[5] Both of the posters below that advertise trips to Japan (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4), feature a woman in traditional kimono, Mount Fuji, and a shrine. There are striking similarities between the Japanese women in these posters and images of the opera, Madame Butterfly, especially in the poster with the body of water in the background. Madame Butterfly, or Chō-chō-san, is the quintessential oriental woman who awaits for her lover, doomed for failure.

Figure 3. “Canadian Pacific picturesque route by fast steamers and trains to Japan and China.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC-GR-00016. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

Figure 4. “Canadian Pacific cruises : information and reservations within.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC_OS_00203. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

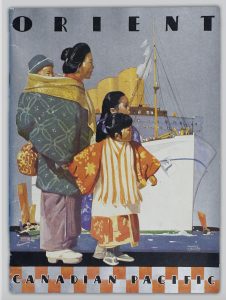

Another rich source is the collection of photographs taken in Meiji Japan by John Cooper Robinson, who was a Canadian missionary. One of Robinson’s objective was to document what he saw during his daily life, living in Japan among the rural Japanese communities. One of Robinson’s favourite themes was taking photographs of people working, such as the photograph of women thrashing wheat while taking care of the children (Fig. 5). There is a remarkable resemblance between John Cooper Robinson’s photographs of women carrying their children on their backs (Fig.6, for more see Allen Hockley’s essay) and the Canadian Pacific Railway poster entitled, Orient (Fig. 7).

Figure 5. “Woman thrashing wheat ’02.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. John Cooper Robinson Collection. RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-2681. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

Figure 6. “[Japanese girls and woman carrying babies on backs].” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. John Cooper Robinson Collection. RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-1620. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

Figure 7. “Orient.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC-TX-284-13. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

Japanese-Canadian Material and Connections to Japan

Students can potentially draw connections between Japanese and Japanese-Canadian material by using multiple related sources from the Meiji at 150 collection. For example, they can examine the Products of Greater Japan woodblock prints from regions where Japanese-Canadians came from. An example of this is the woodblock print of the Ōmi region, which is the current Shiga prefecture where the largest portion of Japanese-Canadians came from.[6] Shiga prefecture is well-known as the producer of Ōmi merchants, who paved the way for modern international trading companies such as Itōchū corporation. Fig. 8 features the Ōmi merchants shipping the mosquito nets, which was one of their prime products that they exported. In 1887, 20 percent (10,000 residents) of Shiga prefecture’s population worked for the production of mosquito nets and linen, and one in five households sold their merchandise outside of Shiga prefecture.[7]

Figure 8. Hiroshige III. “Ōmi no kuni hamakaya yushutsu no zu.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L2:2. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

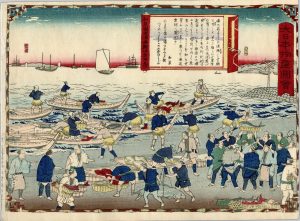

Fig. 9 which depicts the fishing industry, is from southern Osaka (city of Sakai), which was not the region where the majority of fishermen who settled in British Columbia came from. However, the southern Osaka fishermen were rivals to the Mio Village (Wakayama prefecture) fishermen, who immigrated to Canada due to their loss of fishing grounds. From the seventeenth century, Mio Village fishermen began fishing in other areas such as the Kanto region (Tokyo and Chiba prefectures), beyond their local waters. In the Meiji period, they also expanded into the Osaka and Ise Bay areas. With improved fishing technologies such as modern trolling, came fierce competition between fishing boats, to which Mio Village fishermen lost to southern Osaka fishermen.[8] Hence, on the one hand, the woodblock print can be used to explain Japanese-Canadian immigration to Canada, whilst it can also be seen as an example of Meiji Japan’s successful modernization.

Figure 9. Hiroshige III. “Izumi no kuni Sakai no ura sakuradai narabini uoichi no zu.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Asian Rare-6 no.L2:11. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

UBC Library also has the Japanese-Canadian Photograph Collection, which spans in time from 1907 Vancouver Race Riot photos to the 1949 WWII internment camp photographs. The 1907 anti-Asian riot photographs were taken to document the damages caused by the riot, in order to assess the reimbursement costs (Fig 10). They can also be regarded as evidence of racial animosity during this era against Japanese communities in Vancouver (for more see Yukari Takai’s essay). Students can also contrast these Japanese-Canadian photographs against the first set of woodblock prints of the Meiji period, which emphasize Japan’s modernity.

Figure 10. “Building damaged during Vancouver riot of 1907 – 461 Powell Street, $1.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Japanese Canadian Photograph Collection. JCPC_36_013. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

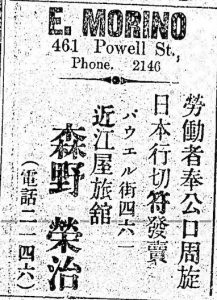

Figure 11. “E. Morino.” February 8, 1908, page 3. Source: UBC Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Tairiku Nippo. PN4919.V23 T3 1989. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

Another noteworthy visual source is the Japanese-Canadian newspaper, Continental Times’ (Tairiku Nippō) advertisements (Fig. 11, see Ayaka Yoshimizu’s essay) which can be used in conjunction with Japanese-Canadian photographs. One of the photographs is that of Ōmi-ya Inn, which from the name indicates that the owner would have connections to the Ōmi (Shiga) region. It is possible to match the photo with the advertisement in the Continental Times and conclude that the owner of this boarding house was Morino Eiji. He was the first president of the Shiga’s prefectural association, which was established in 1905 with approximately 300 members.[9] The advertisement then provides more details such as the fact that the inn also sold tickets to go to Japan, and also acted as an employment agent.

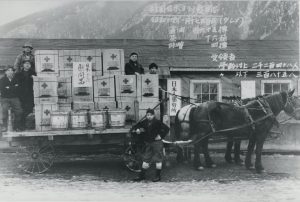

What is also noticeable in some of the visual records left by the Japanese-Canadian communities are the Japanese language material, which are often lost due to language barriers (see Eiji Okawa’s essay on language and identity for related issues). It is also striking to note that there are visible connections with Japan, as can be seen in the photograph from the Tashme internment camp during WWII (Fig. 12). The photograph shows relief items shipped by the Red Cross through Shinwa-kai, which was an elected committee that acted as a liaison between the camp residents and the BC Security Commission.[10] The hand-written caption in this photograph notes, “from the home country Japan, relief goods,” with the list of items including tea, miso, and soy sauce. They are to be distributed in Tashme Camp in 1944, for 2,248 school-aged and above and 385 below school-aged. The vehicle is parked in front of the “Japanese office,” and the barrels of soy sauce and miso have a poster-sized label that reads, “relief items from Japan.”

Figure 12. “View men with horse and wagon at Tashme Camp.” Source: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections, Japanese Canadian Photograph Collection, JCPC_29_003. (Click to enlarge, or view source here).

In this essay, in order to reveal the intersections of Japanese and Canadian histories, I have chosen to examine the various archival collections together, under the umbrella of Meiji. The multiple perspectives presented through our collection of visual essays also cross traditional nation-centered boundaries and categories. For instance, the Japanese-Canadian Photograph Collection would fall under Canadian or Japanese-Canadian; Chung Collection under Chinese-Canadian or Asian-Canadian History; and the Meiji-era woodblock prints would be considered Japanese History. Our Meiji at 150 collection lends us with opportunities to discover possible connections that may have been less visible under different umbrellas.

References

[1] Smith, Lawrence, “Japanese Prints 1868-2008” in Thomas Rimer Since Meiji: Perspectives on the Japanese Visual Arts, 1868-2000, (Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 2001), 6.

[2] Masayuki Handa, “Foresight for Modernization: Roots of ‘Monozukuri’ Interpreted through Agricultural Materials, Technological Writings and Nishiki-e.” The Research Institute for Innovation Management, Hosei University, Working Paper Series. 45 (October 2007): 37.

[3] 松尾正人『日本の時代史21明治維新と文明開化』(吉川弘文館、2004年)255ページ。

[4] 浅野智子「大日本物産図会」と殖産興業政策」(『日本美術研究 (錦絵特集 論文編)』、2002年、18 – 32ページ)。

[5] Mark H. Choko, Canadian Pacific: Creating a Brand, Building a Nation (Berlin: Callisto Publishers GmbH, 2015), 11.

[6] 末永國紀『日系カナダ移民の社会史:太平洋を渡った近江商人の末裔たち』(ミネルヴァ書房、2010年)34ページ。

[7] 末永國紀、 47ページ。

[8] 谷奈々『和歌山の「アメリカ村」とカナダ移民』和歌山社会経済研究所、2008、 http://www.wsk.or.jp/report/tani/13.html(アクセス2018年9月9日)。

[9] 松宮哲『松宮商店とバンクーバー朝日軍:カナダ移民の足跡』(サンライズ出版、2017年)43ページ。

[10]Nikkei National Museum. Tashme 1942-1946 Historical Project. http://tashme.ca/camp-organization/

About the Author

Naoko Kato is Japanese language librarian at the University of British Columbia. She completed her PhD and her Master of Science in Information Studies degree at the University of Texas at Austin. Her doctoral dissertation, “Through the Kaleidoscope: Uchiyama Bookstore and Sino-Japanese Visionaries in War and Peace” (2013), is a transnational history that focuses on Sino-Japanese networks surrounding a bookstore in Shanghai during the first half of the twentieth century and touches upon Pan-Asianism, Christianity, and the peace movement.

Faculty of Art

Faculty of Art