Eiji Okawa

University of Victoria

Japanese-Canadian history is most often discussed in terms of mistreatment of the minority by the Canadian state and society. Indeed, Japanese immigrants and their children were subject to explicit and legal forms of racist marginalization and exclusion throughout the first half of the twentieth century. The outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941 brought Canada’s anti-Japanese policies to unprecedented heights. The government established what it called the “protected area” along the Pacific coast to expel from it all “persons of the Japanese race” irrespective of their citizenship status. What followed were internment, forced sale of properties they had to leave behind, as well as their dispersal east of the Rockies. Nearly 4,000 Japanese Canadians were even exiled to war-torn Japan, a country many of them, born and raised in Canada, had never seen. The community was destroyed and their rights were blatantly violated in this shameful chapter of Canadian history. [1]

This history of injustice is vital to our society especially in the face of entrenched discrimination and inequality persisting to this day. However, in contrast to the prominence of the narrative of victimization in established historical accounts, the social history of the community tends to be overlooked. You don’t have to know anything about a minority to understand they were oppressed, after all. But like any other community, Japanese Canadians have fascinating stories to tell, and these can be analyzed in their own right to enrich our engagements with history. Aiming to provoke interests in sociohistorical experiences of Japanese Canadians and records thereof, this essay looks at the associational lives of several women in the Japanese-Canadian community during the early to mid-twentieth century.

O’Melia-san

O’Melia-san was a white Catholic Nun who dedicated much of her adult life to Japanese immigrants and their community. This is attested to by her grave, situated in the “East Asian” section of Vancouver’s Mountain View Cemetery, where graves of Nikkei persons as well as Chinese Canadians are clustered together.[2] O’Melia-san’s tomb is surrounded by those of Japanese Canadians. It was her wish to be with them, and so when she died of heart-attack while giving a catechist lecture in 1939 she was buried there. Of course, a cemetery is a place of symbolic significance. Among the most grandiose Nikkei tombstones is a towering twelve-foot stupa, built in 1934 with funds raised by a Buddhist Youth Association. It is dedicated to migrants who died in Canada without any relative or family member to offer them ritual care. During the Obon festival of the dead in August, Japanese Canadians make homages to deceased members of their community. O’Melia-san is there, blended as she is into the ritual landscape of the community.

The Japanese inscription in the middle says “O’Melia-san’s grave, built by Japanese volunteers.” Beside her stone is Sister Antoinette McDonough’s (d. 1985), built by “Japanese community and friends.” These women belonged to Franciscan Sisters of Atonement and ran convents serving Japanese-Canadian communities in the prewar era.

Kathleen F. O’Melia was born in Norfolk, England in 1869.[3] She arrived in Vancouver in 1902. Soon, she began working with Japanese migrants. In 1928, she was ordained in the Sisters of Atonement, which purchased a building at Cordova and Dunlevy Street in Vancouver’s Japanese neighbourhood, around Powell Street. That happened to be right next to Oppenheimer Park, where the famous Nikkei ballclub Vancouver Asahi put on great shows of tactical baseball against big-swinging players of local teams.

As a Franciscan nun, her formal name was Sister Mary Stella, but Japanese Canadians continued to call her O’Melia-san. Earnest in her religious calling, she proselytized her faith to migrants but also offered services for the community, including English classes, daycare, and kindergarten. These catered to working mothers. It is said that about 275 children attended her kindergarten and daycare in the first year.[4]

Fig. 3: A group photo in front of Catholic Japanese Mission on Dunlevy Street in Vancouver, taken ca. 1930. O’Melia-san is standing in the middle of back row. Tasaka Family Collection, NNM 2011.83.1.5 (Click to enlarge).

Sister Antoinette McDonough, who worked alongside O’Melia-san in the 30s, writes of her as follows:

She encouraged and inspired us with her great love and zeal for the Japanese people. Sister visited the sick in their homes and hospitals, she taught Religion and English, went begging, acted as interpreter and any other work that needed doing. Nothing was too much for her. I was fortunate to be her companion almost daily on her visits to wherever duty called, and so my first year in Vancouver passed very quickly and I hope not without catching some of Sister Mary Stella’s charisma.[5]

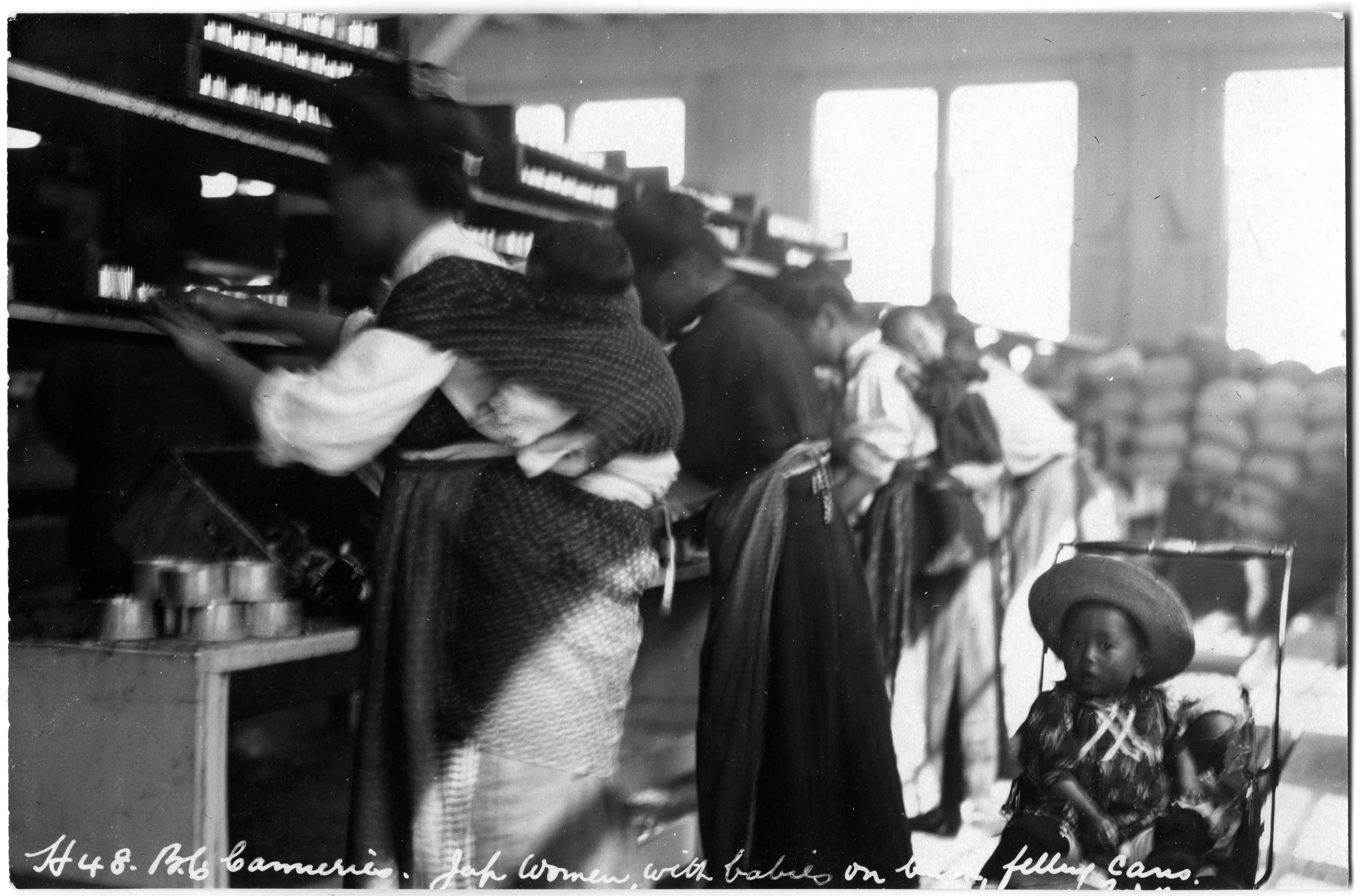

In addition to the “Sister’s Place” on Cordova Street, O’Melia-san opened another convent in Steveston, a fishing village south of Vancouver home to many fishers who came to Canada from Mio village in Wakayama prefecture. With Sister Antoinette, O’Melia-san walked door to door in Steveston to let women know about the daycare services they were offering. By 1934, there were sixty babies in the nursery and eighty children attending Sunday School.[6] Many women working in canneries could leave their toddlers with O’Melia-san rather than carrying them on their backs as they toiled on the production lines earning income for their families. O’Melia-san learned to speak Japanese with Wakayama dialect just like the women around her did.

Fig. 4: Japanese women in a Steveston cannery working with babies on their backs in 1913. Photograph by F. Dundas Todd. Vancouver Public Library 2071 (Click to enlarge).

The Catholic Sisters’ involvement with the community continued after O’Melia-san’s death and into the internment era. When the removal of Nikkei people from the coast was announced early in 1942, Friars of the Franciscan order negotiated with the mayor of Greenwood in the interior to set up residential quarters for internment. [7] That is why many people from Steveston went to Greenwood, and Sisters moved with the community. Some rode on the same trains carrying people away from their homes in a seventeen-hour ride, in which internees, including mothers and infants, were prohibited from leaving their cars. Sisters did what they could to help along the way. Some nuns had gone to Greenwood ahead to help set up the camp and welcomed the arrival of people from Steveston. As Nikkei children were not permitted to attend public schools, Sisters opened a school and kindergarten and provided care and education for children and adolescents. They taught English grammar, high school courses, and even business and piano. As a result, students did not suffer from a lack of education and went on to succeed in various careers in mainstream Canadian society in the postwar era.

Women’s Associations

The Japanese Women’s Association (Nippon Fujinkai) was founded in Vancouver in 1904, seventeen years after the arrival of first known Japanese woman in Canada and had over 170 members by 1907.[8] With the growth and diversification of Nikkei communities and enclaves, there were at least nine Japanese Women’s Associations in British Columbia by 1921. The largest of these were the Japanese Women’s Association, the Buddhist Women’s Association (Bukkyō Fujinkai), and the Christian Women’s Association (Kirisuto Fujinkai). Haney, Steveston, Fraser Mills, Ocean Falls, New Westminster, and Swanson Bay were all homes of regional women’s associations. Members of these associations worked tirelessly to support immigrants and their community. Aspiring for public good, they led charity campaigns and raised funds for hospitals as well as schools and kindergartens. They also sent relief and aid to Japan, extending support to those affected by natural disasters as well as bereaved members of soldiers who lost their lives in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). They also held discussions on various topics over afternoon teas, at times with members of white women’s associations.

A photo of Japanese Women’s Association from ca. 1910 (fig. 7) shows women wearing fine dresses and fancy hats with flowers, suggesting that prominent women took part in this association.

Children also typically appear in photographs of Women’s associations, such as the one taken in front of Japanese Buddhist Church in Vancouver in 1920, found in UBC library’s Japanese Canadian Photograph Collection (fig. 8). The women in this photo were most likely members of the Buddhist Women’s Association, who gathered with some of their children at the church for their meetings and events.

Fig. 8: Source: UBC Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Japanese Canadian Research Collection, JCPC 39.001 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here).

Women’s Associations also organized events for special and ceremonial occasions such as the emperor’s birthday, receptions for dignitaries from Japan, and other celebrations. Below is a photo from a kanreki celebration, or sixtieth birthday of members of the Buddhist Women’s Association, taken in Vancouver in 1939.

They also sponsored floats paraded during festivals.

Unfortunately, there is paucity of records on women’s associations. What’s available are accounts about them written by men rather than records produced by women themselves. Probably the most comprehensive of such accounts are found in Nakayama Jinshirō’s 2,036-page magnum opus on the immigrant community, Kanada dōhō hatten taikan, published in 1921.[9] Nakayama chronicles meetings of the associations as well as their major projects and achievements. For instance, in 1909, Japanese Women’s Associations raised over $1,000 for Vancouver City Hospital, and cleared outstanding medical bills that migrant patients couldn’t pay themselves. In 1919, three Japanese women’s associations contributed about $5,000 in a public charity campaign for the same hospital. Such charitable works were indispensable as government funding for basic medical care was insufficient. During WWI, immigrant men managed to work around a ban from serving in the Canadian military and formed a voluntary corps that fought courageously alongside the Allies in Europe. To support their efforts, the Japanese women’s association in Haney worked with the Canadian Red Cross and sent special care packets consisting of bandages, pajamas, socks, and undergarments for wounded soldiers.

As Nakayama puts it, women empowered the community to transition from a collective of temporary dekasegi workers to permanent settlers, and women’s associations made great contributions to the progress of Japanese peoples on the frontier land. But these associations were highly institutionalized. Japanese Women’s Association, for instance, had a president and ten women sitting on board for three-month terms. It even had an anthem sung during meetings. Women’s associations, then, represent a formalized mode of women’s network practices. Are there records that speak to more informal associational practices among women and their cohorts?

Hanako’s Diary

Fig. 11: Hanako and Tsutae Sato in 1921. Canadian Centennial Project Fonds, NNM 2010.23.2.4.472 (Click to enlarge).

Hanako Sato (née Awaka) taught at the Vancouver Japanese Language School on Alexander Street from the 1921 to 1966, though she farmed in Alberta for about a decade after the school was shuttered by the government in December 1941. Together with her husband Tsutae, she devoted her life to the education of Canadian-born Nisei (second generation). Two years into her professional career as a school teacher in Tokyo, at age twenty, Hanako accepted a job offer from the Alexander Street school and decided to move to Canada. The offer included a marriage arrangement with Tsutae who was just promoted to principal. She knew him as teacher of her younger brothers.

Hanako’s heart pounded in excitement at the idea of moving abroad. But she was concerned about her beloved and widowed mother whose approval she sought. The mother needed a night to think. After a sleepless night of deep reflection, the mother told Hanako she trusted her to make her own decisions. Then she went to Suitengū shrine in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, to get her daughter a special protective amulet as her memento. The amulet was presented to the altar of deceased father, then handed to Hanako the day before her departure. She held it dearly for the rest of her life. On May 12th, 1921, merely a month after first hearing about the offer, Hanako boarded SS Arizona in Yokohama. Standing on the vessel’s deck, she saw and heard her students shouting and cheering from the wharf, “Awaka-sensei!” again and again. The mother did not come, for, being raised in a soldier’s household, she found it shameful to shed tears in public. Clasping the amulet tightly, Hanako bid farewell to Japan and set sail for Canada.[10]

Hanako’s life in prewar Vancouver overlapped with the “golden age” of their school. With the growth of the community, student enrolment increased from about fifty in 1909 to roughly a thousand by 1941, becoming among the largest Japanese-language school in North America. [11]

However, Japanese language schools were often targeted by anti-Japanese politicians who made their careers by pitching exclusionary campaigns, taking advantage of the fact that the unpopular minority lacked political representation. A crisis came in January 1941 when the provincial government initiated a legal measure imposing restrictions on foreign language schools. To make matters worse, City of Vancouver alderman Halford Wilson launched a movement to close Japanese language schools. He alleged the schools were not only backed by the Japanese state and prevented children from Canadianizing but also posed health threats to students. [12]

City Council established a Special Committee and summoned Tsutae for interrogation. Facing Wilson, Tsutae dismissed links with the Japanese government and explained the importance of the school for the community, stressing, as he always had, that the mandate of his school was to raise children into good citizens of Canada.

Wilson’s move lost momentum. But the authorities demanded the schools adopt new textbooks, as the ones in use were too imperialistic. This prompted Tsutae to go to Japan to gather materials for textbook compilation, which would have been fine were it not for the escalation of tension between Japan and the US in the summer of 1941, just days after Tsutae’s departure. As a result, ships from Japan were prohibited from entering North American ports. Tsutae’s return became uncertain, all the while the contending states appeared locked on a collision course. Eventually, Tsutae returned to Vancouver aboard Hikawa Maru just before Japan and Canada entered war.

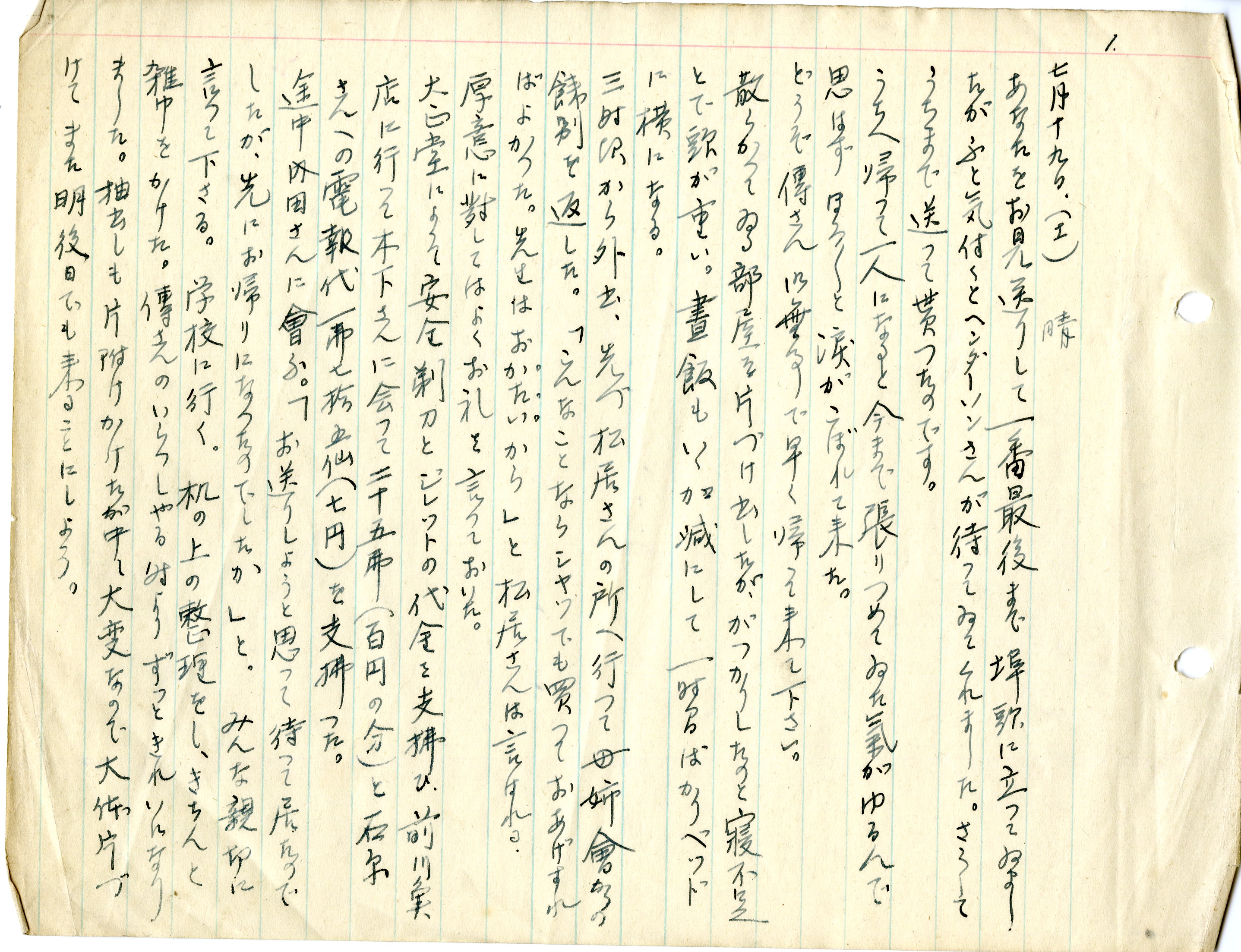

Hanako’s diary begins July 19th, the day Tsutae left for Japan. She missed him dearly and she dreaded nothing more than the spectre of separation by the imminent hostilities she sensed in the air. Everyday she followed the news, hoping to see the lifting of the ban of ships from Japan. She wrote and telegrammed him. Board members of the school urged him to return as soon as he possibly could. She called him as well, speaking to him briefly in English through an operator in San Francisco. The choppy phone line cut their conversation when he uttered, “If I can’t go…”

Amidst disconcerting circumstances, Hanako was comforted by visitors who came to see her daily. People in the community did what they could to support her. Not only did they call her all the time and dropped by her place with gifts and treats, they also sent their girls to stay with her so she did not have to spend nights alone. Below are brief excerpts from her diary (translated by the author):

Jul 19

The house is now empty and lonesome. If I stayed still, sadness overwhelms me. So I found places to clean here and there, and kept myself busy. At night, I worked on the accounting book, but my mind wasn’t clear. So I went to bed. I was in bed by 11. I couldn’t sleep. Tsutae-san kept on coming up on my mind. I wonder if the ship reached the Pacific and is now rolling in big waves. I pray for a safe voyage. The thought of spending the next two months alone makes me anxious.

Jul 20,

Ochiai’s mother called. She said to me, “The night when you send off [your husband] is very sad and lonesome. Last night, I wanted to send Kayo to your place but couldn’t because of a little incident on our end. I will send her along today in the afternoon.”

Just past two, Kayo-san came with some gladiolus. She asked if there was anything she could help me with, so I asked her to write names on pay envelopes. It turned out that the incident yesterday had to do with canned grapefruits that she and her family ate. Kayo’s father became sick from it. Kayo-san was not affected too badly, but her father, with his poor health, vomited and suffered badly. When I hear a story like this I can’t help but to hope that Tsutae-san would not eat foul food. I was going to ask Kayo-san to have some dinner, but her stomach is still not well. So she went home by evening.

Satō Matsue-san and Shizu-chan called me, too. They said, “I had no idea sensei went back. Had I known, I would have gone to the port to see him off…” Shizu-chan said she’d love to come by for a visit on Sunday.

Jul 21

When I got home, your letter was in the mailbox. I read it again and again. It’s only been three days since you left, but it feels like we haven’t seen each other in eternity. You are concerned about me. As you tell me, Tsutae-san, I won’t push myself too hard. I need to stay healthy and take care of the house and school for fifty days during your absence. You are concerned about me being alone at night. But starting tonight, Sadako and Kinuko, Tsuji’s children, will be staying with me at night. When I spoke with Mrs. Tsuji about your trip, she said that her children are free and can help me with anything I might need. Aoki-san, too, was concerned about me being alone. She spoke with Tsuji-san about that, and they decided to get the two of them—Sadako and Kinuko—to come and stay with me.

Michiko from Aoki-san’s stayed with me for dinner and left at around 9:30. We had dinner together. At around 10, Sadako and Kinuko came over with pajamas. Mrs. Tsuji said that Iwata-san nowadays begins work around 7 in the morning so Sadako has to go home at 6:30. Therefore, we went to bed right away. It was odd for me to go to bed when it was still not completely dark. But I was so relieved to have someone stay at the house with me.

July 22 (Tues) Sunny

The alarm went off at 6:30. Sadako and Kinuko went home. I could have gone back to bed, but no, I got up. Just when I was ironing some clothes, Michiko came over. “Did you come alone?” I asked. “Mama dropped me off at Victoria [drive]” She stayed until noon. She played with dolls, then went outside in the back yard to pick flowers. She also danced there. We chitchatted. Thanks to her, I didn’t feel lonely at all…

After dinner, Tanaka Kiyoko-san phoned. She said, “I heard sensei went to Japan. It must be lonely without him. We will come over now to keep you company.” Soon she came with Mieko. They brought some toffy candies and stayed until about nine in the evening. I’m very grateful that everyone is concerned about me, and treating me kindly.

In the evening, I chatted with Mrs. Yakovich on the veranda.

“Where did your husband go?”

“To Japan.”

“To Japan? German submarines are sinking ships with torpedoes these days, you know. Isn’t it dangerous for him to be going to Japan now?”

“I think the Pacific is safer, relatively speaking.”

“Why didn’t you go too? Are you afraid, because Japan is fighting war?”

“….”

Tsuji-san’s children came around nine. They looked at photographs, and we talked. After about an hour, we went to bed.

Community and Associational Practices

These are snippets of associational practices of Nikkei women in the prewar community in the Lower Mainland. What comes to the fore is the diversity of their positions and roles as well as modes of interactions shaping communal structures and historical experiences. O’Melia-san and her fellow Sisters remind us that the community was not isolated from mainstream society. These white women engaged and contributed to the community and helped to embed immigrant lives into the fabric of the broader societal environment. Members of women’s associations networked extensively among themselves and with other organizations such as ubiquitous Prefectural Associations (kenjinkai), white women’s associations, and hospitals. They organized themselves to address social issues and to direct the resources of the community toward common public good.

Rather than being confined to homes and matters on the domestic front, women were a key force in the community’s public life. All the same, Hanako’s diary suggests that homes could be loci of important social interactions. Hanako, to be sure, was a prominent public figure, but her relational practices extended beyond her professional roles as an educator. Her diary is filled with emotions and affects lacking in more formalized records, offering glimpses of rich human experiences as well as robust networks helping Hanako navigate uncertain times.

Fig. 13: Hanako and children enjoying themselves during an outing ca. 1920s. Perhaps this was a school picnic. Canadian Centennial Project Fonds, NNM 2010.23.2.4.713 (Click to enlarge).

Social networks cultivated and sustained by these women were integral to the Nikkei community that once thrived in coastal Canada. Indeed, the community was a dynamic complex of associational practices like the ones touched on above. Records from the past speaking to actions and interactions of women in the community are numerous and diverse. Paying attention to their voices, we can gain fuller understandings of the history of Canada’s diverse society as well as Japanese immigrant experiences.

Endnotes

[1] For works on Japanese-Canadian history with a focus on racist politics and wartime policies, see Ken Adachi, The Enemy that Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1976); Ann Gomer Sunahara, The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War (Toronto: J. Lorimer, 1981); Patricia E. Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1989); Roy, The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941-67 (Vancouver: UBC press, 2007); and Roy, J. L. Granatsein, Masako Iino, and Hiroko Takamura, Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese during the Second World War (Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto press, 1990). Greg Robinson provides a comparative analysis of Canadian and American treatment of persons of Japanese heritage during the Second World War in his A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009). For essays on Nikkei histories in Canada and America, see Louis Fiset and Gail M. Nomura, eds. Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans & Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century (Seattle: Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest in association with University of Washington Press, 2005).

Some of these historiographies were closely related to the postwar activist movement to seek formal apology and redress from the Canadian government for its wartime mistreatment of citizens of Japanese lineage. Redress, achieved in 1988 with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney offering a formal apology in the House of Commons, was a momentous event in Canadian history. For developments of the redress movement, see Roy Miki and Cassandra Kobayashi, Justice in Our Time: The Japanese Canadian Redress Settlement (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1991); Roy Miki, Redress: Inside the Japanese Canadian Call for Justice (Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 2004).

Tatsuo Kage discusses the exile of Japanese Canadians in 1946 with rich oral historical accounts in his Uprooted Again: Japanese Canadians Move to Japan after World War II, trans. Kathleen Chisato Merken (Victoria, BC: Ti-Jean press, 2012, orig.pub. in Japanese Akashi shoten, 1998).

Oral historical approach has been immensely important in recent discussion of Japanese-Canadian history. For studies employing oral historical methods, see Pamela Sugiman, “Memories of Internment: Narrating Japanese Canadian Women’s Life Stories,” The Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie, 29/3 (Summer 2004), 359-88; Sugiman, “’Life is Sweet’: Vulnerability and Composure in the Wartime Narratives of Japanese Canadians,” Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d’Études canadiennes, 43/1 (Winter 2009), 186-218; and Mona Oikawa, Cartographies of Violence: Japanese Canadian Women, Memory, and the Subjects of the Internment (Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto press, 2012).

Important contributions to Japanese-Canadian history by community historians include Roy Ito, We Went to War (Stittsville, ON: Canada’s Wings, 1984); Ito, Stories of My People (Hamilton, ON: S-20 and Nisei Veterans Association, 1994); and Masako Fukawa with Stanley Fukawa and Nikkei Fishermen’s History Book Committee, Spirit of the Nikkei Fleet: BC’s Japanese Canadian Fishermen (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Pub., 2009).

The dispossession of Japanese Canadian is being comprehensively examined and analyzed by researchers of Landscapes of Injustice, a collaborative research project of which the author is a part as a postdoctoral researcher. Recent works by Landscapes researchers include Jordan Stanger-Ross and Landscapes of Injustice Research Collective, “Suspect Properties: The Vancouver Origins of the Forced Sale of Japanese-Canadian-Owned Property, WWII,” Journal of Planning History 15/4 (2016), 271-89; Stanger-Ross and Nicholas Blomley, “’My Land is Worth a Million Dollars’: How Japanese Canadians Contested Their Dispossession in the 1940s,” Law and History Review 35/3 (2017), 711-751; Eric M. Adams, Jordan Stanger-Ross, and Landscapes of Injustice Research Collective, “Promises of Law: The Unlawful Dispossession of Japanese Canadians,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 54/3 (2017), 687-740; Stanger-Ross and Sugiman, eds., Witness to Loss: Race, Culpability, and Memory in the Dispossession of Japanese Canadians (Montreal & Kingston; London; Chicago: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017; and articles in the Journal of American Ethnic History special issue with Landscapes of Injustice forthcoming in summer of 2018. In addition to academic studies, Landscapes is developing teacher resources, museum exhibit, and public history as well as archival website to share research findings with public audiences. Witness to Loss also has a website providing compelling records of a Japanese Canadian man involved in the Canadian policy to dispossess people in his community. These are merely a selective sample of the wealth of works and literatures on Japanese Canadian history.

[2] Nikkei means persons of Japanese lineage. In this essay, this term is used to refer to Nikkei persons in Canada, and is largely synonymous with Japanese Canadians.

[3] For studies of O’Melia-san, see Jacqueline Gresko, “O’Melia San and the Catholic Japanese Mission, Vancouver, B.C.,” Historical Studies 75 (2009): 83-100; Deborah Rink, Spirited Women: A History of Catholic Sisters in British Columbia (Vancouver: Sisters’ Association Archdiocese of Vancouver, 2000), 216-20.

[4] Lurana Kikko Tasaka, “An Unforgettable Past—A Time to Remember—With Gratitude,” The Bulletin Geppō, Jul.1996, 12.

[5] Cited in Rink, 219.

[6] Gresko, 94.

[7] Rink, 220-25.

[8] My source on the history of women’s associations is Nakayama Jinshirō, Kanada dōhō hatten taikan, zen [Encyclopedia of the Progress of Japanese in Canada] (1921), 1683-1702, in Sasaki Toshiji and Tsuneharu Gonnami, eds. Kanada iminshi shiryō, vol. 8. Tokyo: Fuji Shuppan, 2000

[9] Ibid.

[10] Tsutae and Hanako Sato, Nikkei Kanada-jin no nihongo kyōiku: zoku kodomo to tomoni gojūnen (Tokyo: Nichibou shuppansha, 1976), 201-207.

[11] Tsutae Sato, ed. Bankūbā nihon kyōritsu gogakkō enkakushi, History of Japanese Language School (Vancouver: Bankūbā nihon kyōritsu gogakkō ijikai, 1954), 91-96.

[12] Sato, 193-218; Tsutae and Hanako Sato fonds, NNM 1996.170.1.6.1/1.

About the author

Eiji Okawa is a social historian specializing in medieval and early modern Japan as well as Japanese diaspora in early to mid twentieth century Canada. He is interested in religious and social institutions, and how people relate to cultural landscapes and organize their society by managing or overcoming conflicts and tensions. He completed his doctoral degree in Japanese history at the University of British Columbia in 2016. Currently, he is a postdoctoral fellow with Landscapes of Injustice as well as University of Victoria’s history department. Landscapes is a collaborative project on the dispossession of Japanese-Canadian properties by the state during the 1940s.

Eiji Okawa is a social historian specializing in medieval and early modern Japan as well as Japanese diaspora in early to mid twentieth century Canada. He is interested in religious and social institutions, and how people relate to cultural landscapes and organize their society by managing or overcoming conflicts and tensions. He completed his doctoral degree in Japanese history at the University of British Columbia in 2016. Currently, he is a postdoctoral fellow with Landscapes of Injustice as well as University of Victoria’s history department. Landscapes is a collaborative project on the dispossession of Japanese-Canadian properties by the state during the 1940s.

Faculty of Art

Faculty of Art