Benjamin Bryce

University of Northern British Columbia

The Canadian Anglican missionary J. Cooper Robinson (1859-1926), an avid amateur photographer, left behind thousands of photographs documenting over 35 years of missionary work in central Japan, mainly in Nagoya between 1888 and 1925.[1] In 2014, some of Robinson’s descendants donated almost the entirety of a private collection – approximately four thousand images recorded on glass plates, film negatives, printed pictures, and postcards – to the University of British Columbia Rare Books and Special Collections library.

This essay is primarily interested in the collection as a private archive: Robinson’s photographs spent most of their time in his and then his family’s possession. As historian Kevin Coleman argues, private and public photo archives have different goals, and it is worth reflecting on not only author and subject but also archival practices when analyzing photo collections. While a creator of private collections may “keep a copy of almost every negative that he produced,” Coleman contends that public collections, made by companies, photojournalists, or governments are “the result of an aggressive attempt to shape” what outsiders see.[2]

The Robinson photographs offer a unique window into life in the Meiji and Taishō eras precisely because the audience and purpose of these photographs are different from many other photos that remain from this period. Robinson surely had motives when taking pictures, but they were significantly different from those of western travellers or missionaries who intended to exhibit or publish their pictures and different from those of Japanese officials or companies that also wanted to document the lives of working and rural people. Cooper Robinson shared the pictures with a small group of people soon after he took them. Yet he saved glass plates or negatives rather than easy-to-view prints, and this suggests that he did not use his private archive to repeatedly share images with others. The glass plates and negatives were stored in a series of family homes, rarely viewed after the photographer died in 1926.

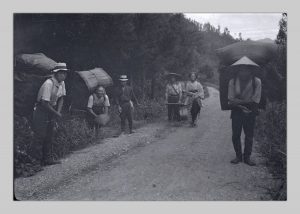

Robinson had a series of themes that he found worthy of documentation. Workers and rural peoples, converts to his Anglican mission, and personal relationships – with his Japanese colleagues and his family – take up a large part of the UBC collection. Shots of Japanese officials, modern cities, industry, historic buildings, or beautiful landscapes do not figure prominently in his project. Robinson, either consciously or not, altered and enlarged a specific image of Japan, whether for himself, his missionary colleagues in Japan, or Anglicans and others back in Canada. But in so doing, he presented one possible vision while hiding other possible ways of seeing the Japanese and the country.

Robinson’s intended audience for the photographs that remained in his private collection is unclear. Was he simply collecting memories as an amateur photographer? The audience of the more than two-hundred postcard prints he had made was surely different than the glass plates in the collection. Did he take many of the pictures with the intention of showing them to Canadians during his furloughs as a way to justify his missionary activities and to raise money for future Anglican activities in Japan? Based on the pictures he took of Canada during his stay in 1919 (also included in the UBC collection), Robinson visited many parts of the country during his furloughs. Did he meet with people to discuss missionary work and did he show his pictures widely during these ephemeral moments? While the vast corpus gives us hints that the photographer knew many of his subjects, he also likely convinced people he did not know or did not know well to pose for the camera.

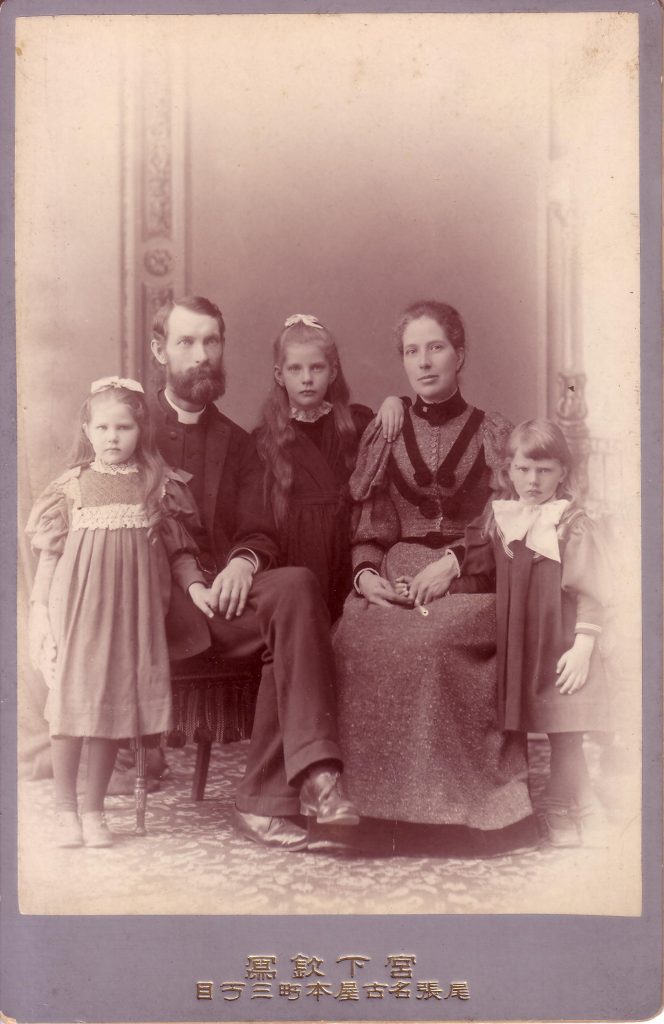

The Robinson Family

Cooper Robinson was born near Blenheim, Ontario in 1859 and graduated from Wycliffe College at the University of Toronto in 1886.[3] His wife Bessie (née Poynton) [4] was born in Nottingham, England in 1858 and immigrated to Toronto in 1881.[5] Together, they went to Japan only months after their marriage in 1888. Robinson worked for thirty-seven years as a missionary in the country with furloughs to Canada every five or six years.[6] Their three children were born in Japan: Lucy Winifred in 1890, Hilda in 1891, and Cuthbert in 1893.[7] It was through Cuthbert’s son Stuart, and then ultimately Stuart’s daughter Jill, that this private collection was preserved and then donated to UBC in 2014.

The expanded Robinson family – now five instead of two – came (back) to Canada for their first furlough in 1894. The family again travelled to Canada in 1902, with Bessie in ill health. Cooper returned to Japan that same year while the rest of the family stayed in Toronto due to Bessie’s health and for their children’s education. After ten years of living apart, Bessie returned to Japan in 1912 accompanied by Cooper and one daughter, the 21-year-old Hilda, but not the 22-year-old Lucy Winifred nor the 19-year-old Cuthbert.[8] Bessie spent another six years in Japan before returning to Ontario with Cooper on a furlough in 1918; she died a year later while still in Canada.[9] Cooper and his daughter Hilda returned to Japan in 1919. Cooper came to Canada on a furlough in 1925, and he died unexpectedly in in Ontario in 1926.

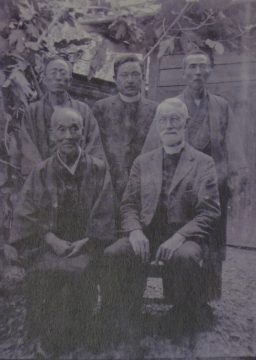

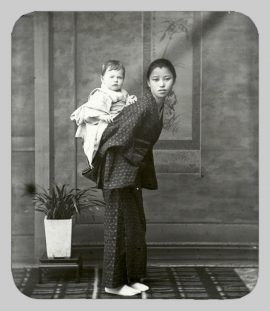

Part of the collection includes pictures – particularly of the young Robinson family in the 1890s – taken at Japanese studios (see Figure 1). Other pictures, which appear to be taken with Cooper’s camera, include him as the subject, and in these cases there are other photographers (see Figure 2). Yet in all three cases (studios, pictures by Cooper, and pictures taken by others using his camera), the collection maintains a certain consistency of documenting personal relationships within the family, and with Japanese converts and other western missionaries. Based on the photos in this collection, it appears that Robinson took up photography in earnest during the ten years he worked in Japan without his wife and children (1902-1912). Since the collection consists largely of glass plates and to a lesser extent film negatives, few of the pictures are labelled.

Figure 2. Bessie, Cooper, and Hilda in garden, taken between 1912 and 1918. Source: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections. “Family in back garden, Sh[inokabi] Cho.” RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-0114. Click to Enlarge.

Figure 3. Students at the Gifu school for the blind, 1921. Source: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections. “Blind school grads 1921.” RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-0284 (Click to enlarge).

In his book, The Island Empire of the East: Being a Short History of Japan and Missionary Work therein with special reference to the Mission of the M.S.C.C (Toronto, 1912), Robinson tells Canadian readers about his success, but he also reveals that a certain amount of isolation shaped his time in Japan. This point can cast more light on the people and things that Robinson photographed and the Japanese subjects who volunteered for the camera. Indeed, many of the subjects of his photographs are the small group of Japanese Christians and foreign missionaries with whom Cooper Robinson spent most of his time (see Figures 4 and 5). Although he framed his work in a positive light, he reported to Canadian readers about the slow progress of evangelizing. When he returned to Canada on his first furlough in 1894 after spending almost six years in the country, he reported that he had baptized thirty-seven people, “four of whom afterwards became his fellow-workers in the Gospel.”[11] In the missions in Toyohashi (68 km southeast of Nagoya) and Ono (135 km north of Nagoya) that Robinson was involved in, he reported that over the course of sixteen years (between 1896 and 1912), sixty-five people had become baptized Christians.[12]

Figure 5. Scenes from Takaragawa trip, 1921. “Scenes on Takaragawa[?] trip [group of Japanese men and women].” Source: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections. RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-0449 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here). |

|---|

Robinson’s Photographs

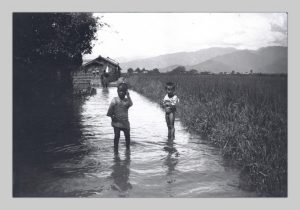

Robinson’s pictures depict a broad range of themes relevant to both foreign missionaries in early twentieth-century Japan and the country more generally. There are portraits and group shots of Japanese people, and many of those people are likely – though not clearly – Japanese Christians. Yet there is also a very large number of smiling vendors, peasants, and workers, and their connection to a Christian denomination or even their relationship with Robinson is less clear. According to historian Margaret Prang, “Protestantism in Japan early assumed the dominantly urban, educated, middle-class character it retained throughout the twentieth century.”[13] Some of Robinson’s Japanese subjects were fellow Anglicans, with whom he clearly had a personal rapport, and apparently fit Prang’s point about middle-class status. Yet many of Robinson’s subjects were poor peasants or street vendors, and are likely people who were not Christian converts and with whom he did not have a personal relationship (see Figures 6, 7, and 8). Those pictures in particular contain a layer of Orientalism and a belief in Western superiority. Susan Sontag has stressed that “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and, therefore, like power.”[14]

Nevertheless, the agency of the subjects – even the peasants and workers who found their way into Cooper Robinson’s pictures – should not be overlooked. The photographer offered these subjects the opportunity to be remembered and to interact with modern technology. To some extent, his subjects may have also known that they would travel, through Robinson’s glass plates or prints, back to Canada and would shape Canadians’ ideas about Japan. Kevin Coleman stresses that rather than seeing a photographer’s subjects as victims of asymmetrical power, “[t]he simple fact that this image exists points to the way that photography can be used by otherwise marginalized people to make modest claims to dignity and to thereby create new ways of thinking, speaking, and acting…Photography enabled the excluded…to see themselves in a new light and to make themselves visible to others.”[15] Robinson’s act of photographing and saving the images was itself an act of empowering a marginalized subject. Coleman adds that while photography has been “a means of surveillance, discipline, and classification,”[16] it also “allowed people with little power or influence to rearrange the signs of their exclusion and purported inferiority such that they could then see themselves, and others could see them, as worthy of respect.”[17]

Figure 6. Men carrying cocoons and Hachiman, 1920. Source: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections. “[Men] carrying cocoons. Hachiman, K[?].” RSBC-ARC-1757-PH-0343 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here). |  Figure 7. Japanese Woman Carrying Babies, 1905. Source: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections. “Japanese girls and woman carrying babies on backs.” RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-1620 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here). |  Figure 8. Children in Canal by Field, 1908. Source: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections. “Children in canal by field.” RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-0043 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here). |

|---|

Family is another important part of the J. Cooper Robinson collection at UBC. There are many portraits of him and his immediate family on their own or with Japanese friends or colleagues (see Figures 2, 4, and 9). Hilda Robinson appears in several photos with Japanese women of a similar age (see Figure 10). The pictures of Robinson himself are generally of a middle-aged man with a grey beard and grey hair. Photographs of his daughter, Hilda, outnumber her two siblings to an astonishing degree. Lucy and Cuthbert left Japan in 1902 to attend high school and later university in Toronto; Hilda did the same but returned to Japan in 1912. Lucy and Cuthbert’s absence and Hilda’s presence date most of the photographs between 1912 and 1925, the years between Hilda’s return to Japan and Cooper’s departure.

Figure 9. Lucy Winifred at 10 months on O Ei’s back, 1891. Source: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections. “Lucy on O Ei’s back, 10 mo[nth]s.” RBSC-ARC-1757-PH-3028 (Click to enlarge, or visit source here). |

Conclusion

The J. Cooper Robinson collection at UBC offers students and researchers several important perspectives on Japanese society, western missionaries, and Canadian internationalism between 1888 and 1925. This private collection offers glimpses of life, work, and landscapes in Nagoya and environs, but the “double testimony” of the photograph also tells us about the photographer himself and about the life and a broader history of Canadian missionary activity in Japan.

As a history professor, I am particularly compelled by the significance of the Robinson collection as a private archive. I am also compelled by a group of scholars’ arguments about the agency of the photographic subject rather than the asymmetrical power relations that were also part and parcel of early photography.[18] Robinson’s subjects were active participants in forging an image of themselves, their regions, and their lifestyles. Despite his own proselytizing motives, he brought a large number of marginalized peoples into the public eye. He helped them be seen and let them pose and show themselves to an audience of which they had at least some degree of knowledge and about which they perhaps had a desire to know more.

Yet as the great-great-grandson of the photographer, researching and writing this essay has been an instructive exercise in subjectivity and objectivity. This personal connection has surely allowed me to be more sensitive to the importance of family relations in the photographer’s work and to think about who’s who and how that mattered. It has also led me to a research methodology that I have not had with other projects. Having the e-mail addresses of Cuthbert’s and Lucy Winifred’s grandchildren has allowed me to check facts. And having an uncle who sent me Bessie’s and Cooper’s obituaries, a father who mailed me a copy of The Island Empire of the East, and an aunt who added important, often personal information about the lives of Bessie, Lucy Winifred, and Hilda sped things up in helpful ways and enriched my analysis. Yet my personal – albeit very distant – relationship with this historical subject has also made me uneasy as a historian. Historians cling to a belief in some degree of objectivity – or shy away from flagging our subjectivity – more than in other disciplines. Yet the act of researching and writing something where I cannot get around my own subject position has been far more help than hindrance.

Notes & References

[1] Robinson worked primarily in Nagoya and Gifu, but he also spent some time in Niigata (425 km north) and Hiroshima (480 km south). “The Rev. John Cooper Robinson, D.D.” The Japan Mission Year-Book, no. 25 (1927). 339.

[2] Kevin Coleman, A Camera in the Garden of Eden: The Self-Forging of a Banana Republic (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2016), 16.

[3] “Rev. John Cooper Robinson, D.D.,” The Canadian Churchman, July 22, 1926, 476.

[4] “In Memoriam: Mrs. J. Cooper Robinson,” The Canadian Churchman, November 20, 1919, 1.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “The Rev. John Cooper Robinson, D.D.” The Japan Mission Year-Book, no. 25 (1927). 338-39.

[7] “Descendants of John Robinson, born 1811.” www.ancestry.ca.

[8] “In Memoriam: Mrs. J. Cooper Robinson,” The Canadian Churchman, November 20, 1919, 3.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Hamish Ion, “The Missionary Connection: Ambassadors of the Cross: Canadian Missionaries in Japan,” 30-47, in Canada and Japan in the Twentieth Century, edited by John Schultz and Kimitada Miwa (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1991), 32; John Meehan, The Dominion and the Rising Sun: Canada Encounters Japan, 1929-41 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004), 23.

[11] J. Cooper Robinson. The Island Empire of the East: Being a Short History of Japan and Missionary Work therein with special reference to the Mission of the M.S.C.C. (Toronto: The Prayer and Study Union of the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada, 1912), 125.

[12] Ibid., 134.

[13] Margaret Prang, A Heart at Leisure from Itself: Caroline Macdonald of Japan (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1995), 24; Prang notes that “former samurai” and their descendants “constituted a large majority of the ministers and lay leaders of the churches, [and] they also accounted for as much as 40 per cent of the total membership (75 per cent in Tokyo), although they were less than 6 per cent of the population [of Japan]” (Margaret Prang, A Heart at Leisure from Itself: Caroline Macdonald of Japan [Vancouver: UBC Press, 1995], 24).

[14] Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1990), 4.

[15] Kevin Coleman, A Camera in the Garden of Eden: The Self-Forging of a Banana Republic (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2016), 4.

[16] Coleman, 28.

[17] Coleman, 4.

[18] Coleman, A Camera in the Garden of Eden; Greg Grandin, “Can the Subaltern Be Seen? Photography and the Affects of Nationalism,” Hispanic American Historical Review 84 (2004): 83–112.

About the Author

Benjamin Bryce is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Northern British Columbia. He received his PhD and MA from York University (2013, 2008) and his BA from the University of British Columbia (2005). His research focuses on migration, education, and religion in Canada and Argentina. He is the author of To Belong in Buenos Aires: Germans, Argentines, and the Rise of a Pluralist Society (Stanford University Press, 2018). He is also the co-editor of Making Citizens in Argentina (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017) and Entangling Migration History: Borderlands and Transnationalism in the United States and Canada (University Press of Florida, 2015).

Benjamin Bryce is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Northern British Columbia. He received his PhD and MA from York University (2013, 2008) and his BA from the University of British Columbia (2005). His research focuses on migration, education, and religion in Canada and Argentina. He is the author of To Belong in Buenos Aires: Germans, Argentines, and the Rise of a Pluralist Society (Stanford University Press, 2018). He is also the co-editor of Making Citizens in Argentina (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017) and Entangling Migration History: Borderlands and Transnationalism in the United States and Canada (University Press of Florida, 2015).

Faculty of Art

Faculty of Art